Climate Change and Food Systems: Transforming Food Systems for Adaptation, Mitigation, and Resilience

Many promising innovations and policy approaches show potential to address climate change in food systems while also increasing productivity, improving diets, and advancing inclusion of vulnerable groups. These range from new crop varieties, clean energy sources, and digital technologies to trade reforms, landscape governance, and social protection programs.

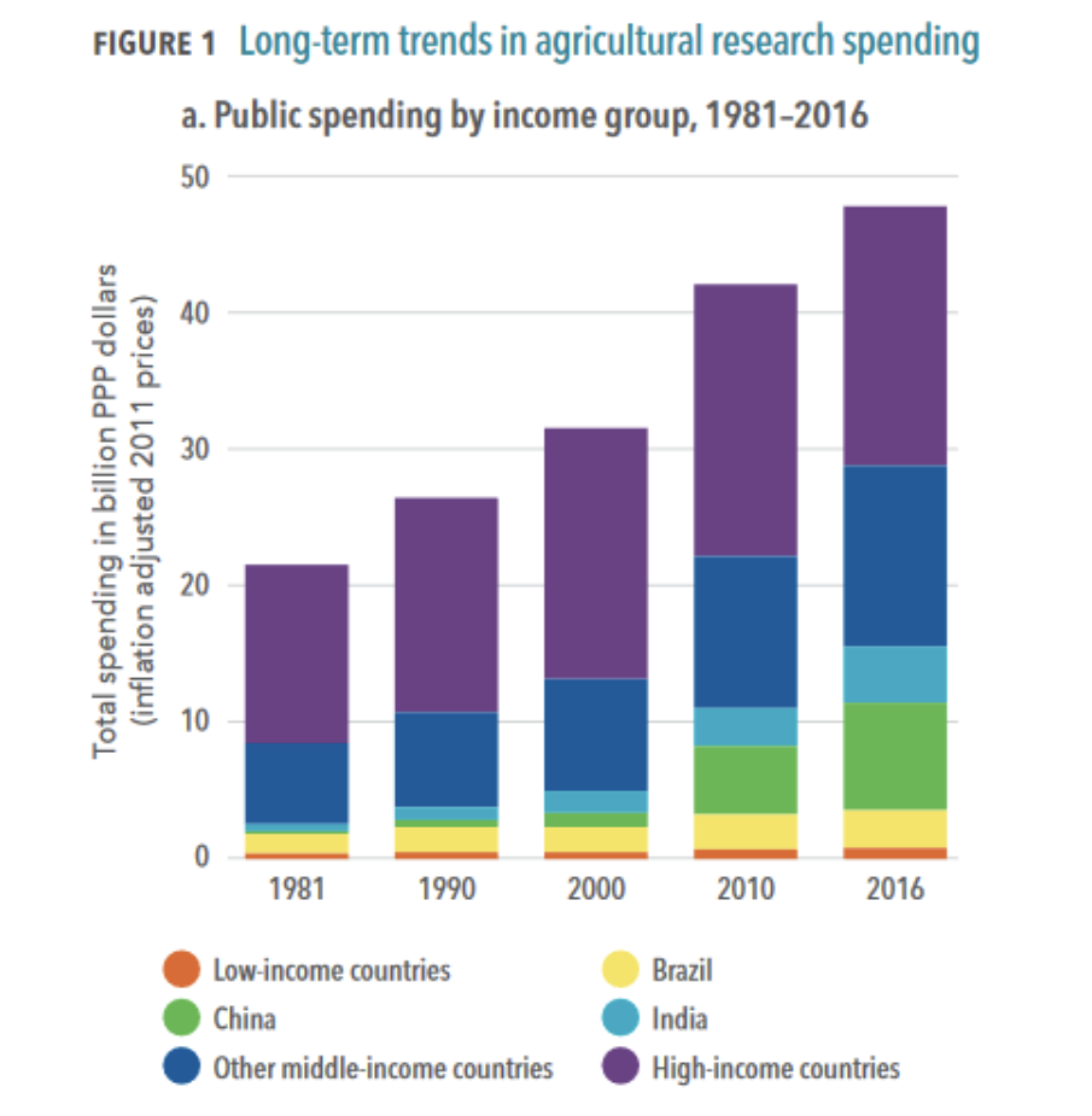

All of these will require substantial increases in funding for R&D and other investments in sustainable food systems transformation.

Food systems policies that create better market incentives, strengthen regulation and institutions, and fund R&D for climate-resilient technologies and practices are needed to catalyze and accelerate climate action.

Repurposing Agricultural Support Creating Food Systems Incentives to Address Climate Change

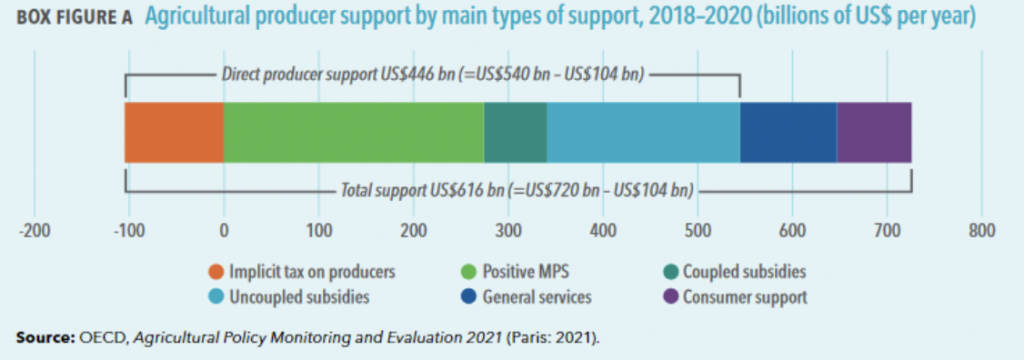

Agricultural support policies transfer around US$620 billion per year to the farm sector worldwide. Most support is provided to larger farmers and appear to increase greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change.

Better outcomes could be achieved if even a small portion of agricultural subsidies were repurposed into investments in R&D dedicated to productivity-enhancing and emissions-reducing technologies. Creating constituencies for reform at the national level and in international forums will be essential to build political consensus for concerted global action.

Trade and Climate Change: The Role of Reforms in Ensuring Food Security and Sustainability

Trade allows countries to obtain nutritious foods at the lowest possible cost, and so will be a key component in any strategy to help countries to feed and nourish their populations. Food imports make up a growing share of low- and middle-income country food consumption.

Free and open trade should be seen as integral to any climate-smart agriculture strategy because, globally, it can lead to a more efficient use of resources and can help reduce GHG emissions from global agricultural production.

To facilitate trade and help to meet global goals for resilience and mitigation, countries should pursue further liberalization of agrifood trade through reductions in tariff and nontariff barriers, trade-distorting domestic support, and export subsidies and restrictions.

Research for the Future: Investments for Efficiency, Sustainability, and Equity

Steps can be taken to ensure that R&D contributes to greater productivity, sustainability, and equity:

-

Increase research investments for food systems in the context of climate change, both on and beyond the farm in low- and middle-income countries;

-

Build cooperation for sharing innovations. Greater integration of food research at the regional and global levels will allow countries with limited domestic research capacity to benefit from the gains achieved by countries with more developed systems;

-

Promote both public and private sector investment.

Climate Finance: Funding Sustainable Food Systems Transformation

Reorienting financial flows to address climate change adaptation and mitigation is one of the key objectives of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

Current financial flows for climate change in the agriculture, forestry, and land use (AFOLU) sector, one of the components of food systems, amount to US$20 billion annually — less than 4 percent of total climate finance.

Estimates of additional funds needed for a climate-positive transformation of food systems plus meeting other Sustainable Development Goals range up to $350 billion per year to 2030.

Important steps can be taken now to increase funding for climate change mitigation and adaptation in food systems:

-

Governments can consider legislating net-zero carbon targets, pricing of climate externalities, development of carbon markets, and disclosures of climate risks as ways to create an effective incentive framework;

-

Guide consumption- and production-related financial flows in food value chains. To reorient consumer spending, governments can influence the food environment using fiscal tools, regulations, and information; investments by food systems operators can be influenced by consumer demand and by taxes, subsidies, and regulations;

-

Use international development funds strategically. Multilateral and bilateral development agencies should be held to their climate commitments, and their

investments can be used to leverage private funds from global capital markets; -

Improve the allocation of national public budgets. To achieve the greatest impact, public funds should be targeted to research and innovation for sustainable intensification of agriculture, as well as investments in science across entire food value chains and the consumer environment;

-

Steer banking systems and capital markets toward climate-positive operations. Climate mitigation and adaptation projects constitute a miniscule share of bank lending and private sector investments, while investments in counterproductive activities remain high.

-

Ensure banking systems and capital markets support inclusive transformation by identifying investable opportunities and targeting credit lines to disadvantaged groups. Small farmers and businesses, women, and youth are most affected by climate change but often lack access to investment funds.

Social Protection: Designing Adaptive Systems to Build Resilience to Climate Change

Social protection programs are a central component of national strategies in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to increase incomes for poor households and protect them from livelihood shocks.

Adaptive social protection (ASP) is an integrated approach that addresses the challenges of climate change by combining social assistance programs with humanitarian assistance and disaster risk reduction strategies. The following steps can strengthen the role of social protection systems in climate adaptation:

-

Expand coverage of existing social assistance to immediately improve resilience of the most vulnerable, reduce hardship, and promote economic inclusion;

-

Reform social protection systems by strengthening coordination between conventional social assistance, humanitarian response, and disaster risk reduction;

-

Undertake risk and challenge assessments, including of contextual factors and climate forecasting, to inform social protection adaptation;

-

Reform program modalities to support household coping strategies, such as using digital transfers that are accessible during local seasonal migration;

-

Make social protection “climate smart,” such as through innovative insurance and productive inclusion initiatives.

Landscape Governance: Engaging Stakeholders to Confront Climate Change

Confronting climate change requires governance at the landscape level where actions are taken that support natural resource management for adaptation and mitigation.

Policy priorities should include:

-

Developing multi-stakeholder platforms (MSPs) to build collective action on climate change. Effective MSPs require investment of time and resources to build a shared vision among actors, as well as to strengthen community and government capacity for cooperative landscape management. Addressing power inequities among landscape-level stakeholders is essential for knowledge-sharing, cooperation, and participation;

-

Strengthen resource rights to support long-term investments. Tenure security, including both individual rights and collective rights over shared resources such as forests and irrigation systems, is essential to create incentives for long-term investments;

-

Devolve resource rights and management responsibilities. Shifting rights and responsibilities to communities can promote locally appropriate actions on climate change and encourage governments to collaborate across sectoral divisions and with communities and the private sector to help address climate change and other goals.

Nutrition and Climate Change: Shifting to Sustainable Healthy Diets

Ensuring that everyone has access to — and consumes — sustainable healthy diets is one of the most significant challenges for today’s food systems.

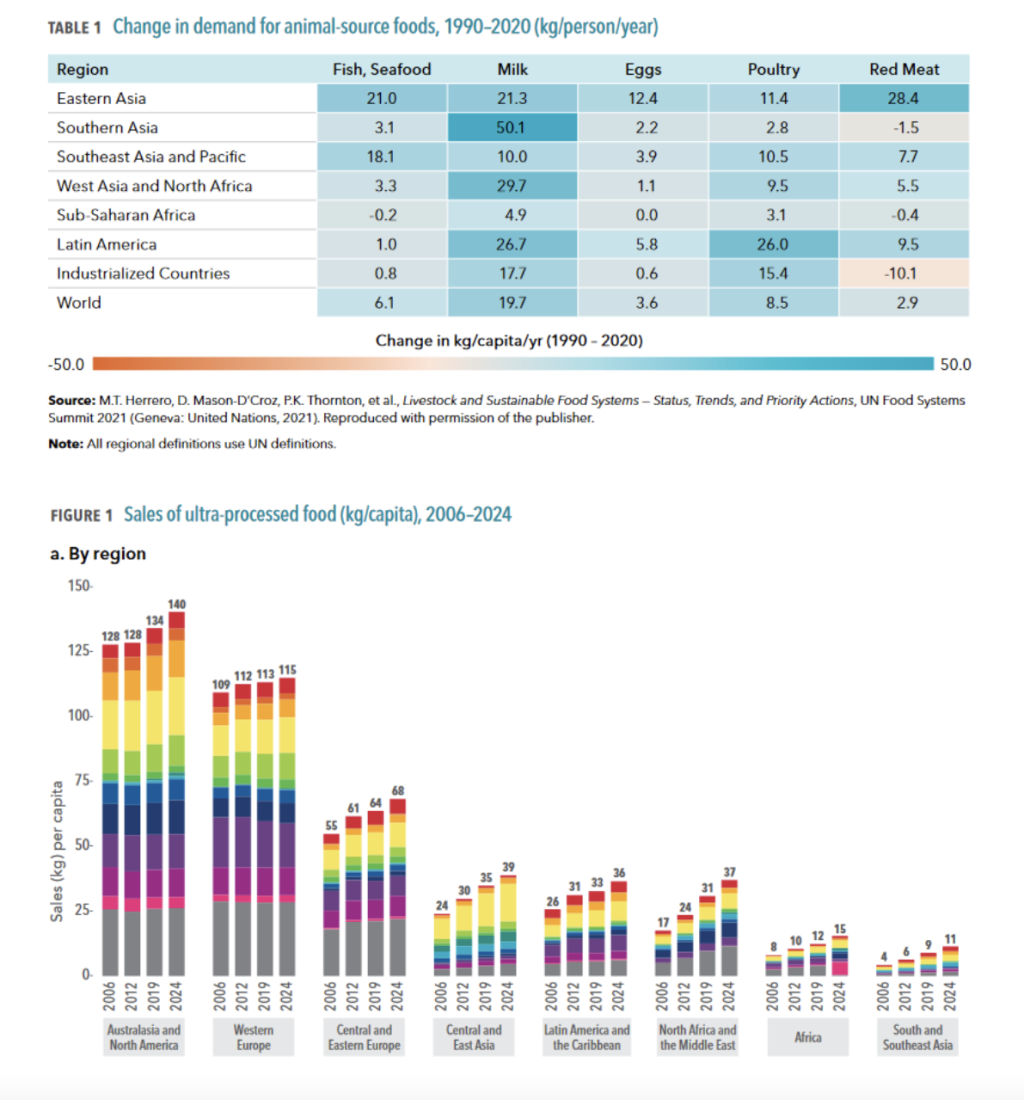

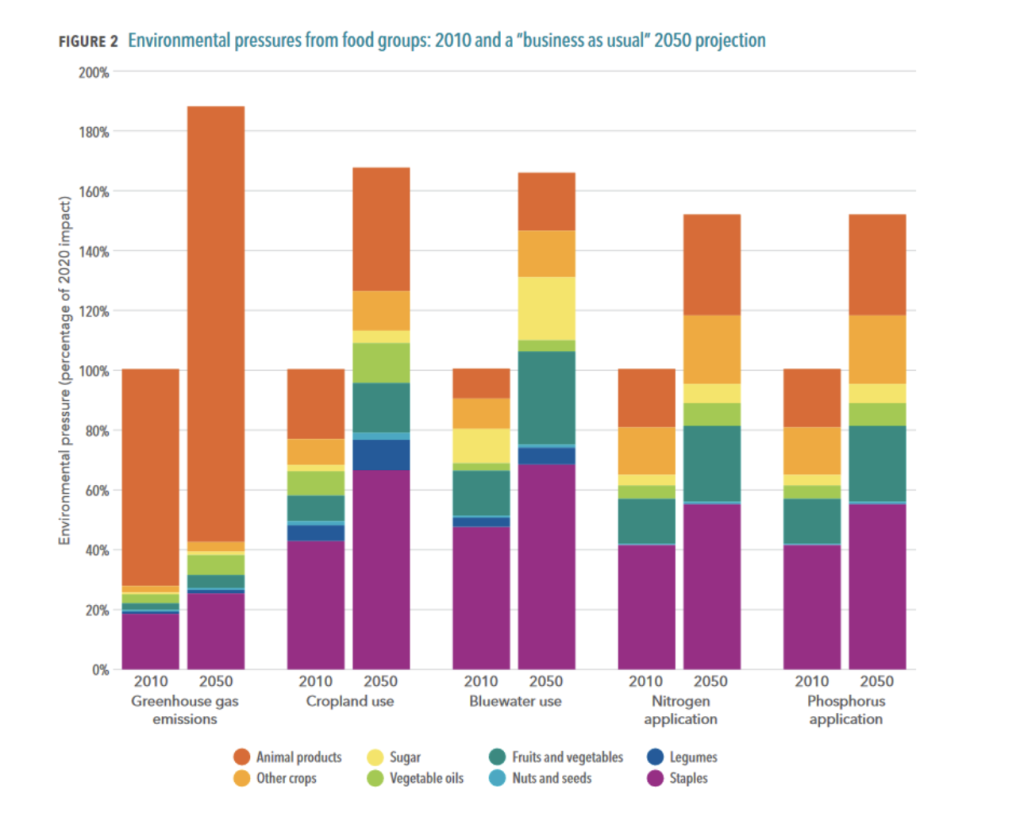

The way we produce, process, and move food, and the global changes in diets toward greater (often excessive) consumption of animal-source foods and ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are contributing to climate change.

The effects of climate change on food systems, diets, nutrition, and health disproportionately impact marginalized populations in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Shifting to sustainable healthy diets that protect both human and planetary health will present several challenges, and among them, their affordability in LMICs.

Policy priorities should include:

-

consumer education approaches. Examples include: education approaches to inform, educate, nudge, and influence dietary choices (public awareness campaigns, nutrition-counseling, mass media, social media, and so on); promotion of breastfeeding; and development and updating of food-based dietary guidelines;

-

Fiscal measures to discourage consumption of unhealthy UPFs, and/or incentives to retailers to subsidize and boost consumption of nutritious foods;

-

Food environment policies, including food labeling and certification, and regulation of marketing and promotion of unhealthy foods to children to enhance demand for healthy diets.

Rural Clean Energy Access Accelerating Climate Resilience

Rural livelihoods in low- and middle-income countries are doubly jeopardized by energy poverty and climate change.

Accelerating a rural clean energy transition will thus be key not only to reducing climate change but also to improving rural lives and livelihoods. Several actions can accelerate rural access to clean, sustainable energy for all:

-

Identify locations where promising energy and water sources and productive uses are in close proximity; this can jointly support energy, water, and food security without compromising ecosystem health;

-

Create an enabling environment for accelerated clean energy development. This requires integrated governance across the water-energy-food-environment sectors. It also requires equitable access to energy through investments, incentives, and direct support for poor farmers and entrepreneurs;

-

Strengthen women’s agency in rural clean energy systems. Promoting a women-centered clean energy program can trigger multiple social, economic, and environmental benefits in rural communities.

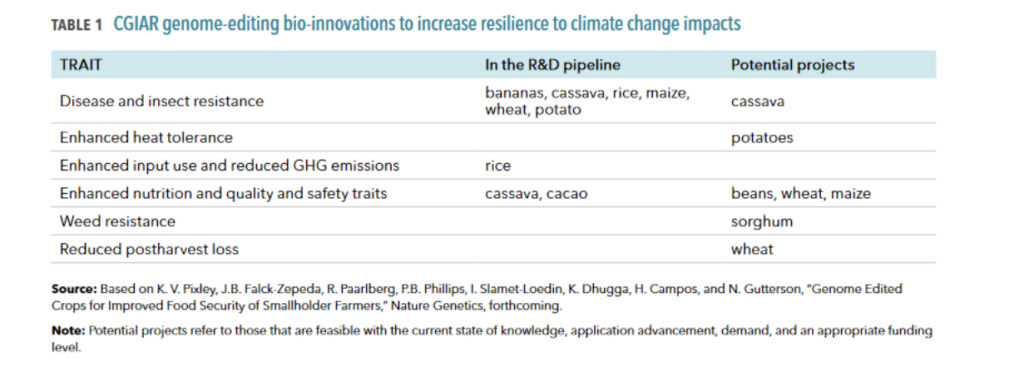

Bio-innovations: Genome-Edited Crops for Climate-Smart Food Systems

GEd allows researchers to rapidly develop climate-resilient and climate-adaptable crop varieties tailored to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Functional and streamlined regulatory frameworks are an important component of any robust enabling environment to create and support incentives for product development and deployment.

Start-ups and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can help drive the democratization of GEd in LMICs, as they have been more agile in implementing GEd R&D processes. Partnerships that enable technology transfers or even generate spin-offs or SMEs are a promising strategy to rapidly deliver new climate-resilient applications for LMICs.

Understanding the needs and preferences of farmers, including gendered needs, for different crop traits, delivery methods, and extension services is essential to the successful development and deployment of Ged products.

Food Value Chains: Increasing Productivity, Sustainability, and Resilience to Climate Change

Higher temperatures and humidity resulting from climate change will lower on-farm productivity and increase food spoilage and contamination along food value chains, with implications for food prices and nutrition.

Three action-ready solutions can begin to address climate change impacts in food value chains:

-

Monitor the impacts of climate change, especially for vulnerable populations. Governments must monitor consumption, with particular attention to ensuring poverty does not increase and diets do not deteriorate;

-

Create an enabling environment for cold chain development. In the value chain midstream, cold chains can reduce food loss and waste.

-

Support simple, low-cost options to reduce aflatoxins.

Digital Innovations: Using Data and Technology for Sustainable Food Systems

Digital innovations offer unprecedented potential for managing climate risks across the entire agrifood system — from producers to markets and value-chain services to policymakers.

Farmers can benefit from localized weather information services, digital extension services, and weather index-based insurance schemes.

Along food value chains, internet-connected sensors can monitor food quality and safety risks, while digital innovations in insurance, credit, and banking can increase access to risk-reducing services for all food system actors.

However, rural food production areas are underserved by digital infrastructure. Hundreds of millions of small farmers, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, do not have mobile network coverage or internet access, and more than 300 million cannot access digital climate advisory services. Women, in particular, have limited access to digital services.

Critical steps to take now include:

-

Invest to bridge the digital divide. Both private and public investment are needed to address this gap. Given low returns on investments in connectivity in rural areas, policy incentives and public-private partnerships should promote private investments that benefit vulnerable populations and are inclusive of women;

-

Strengthen agrifood information systems. Digital technologies can provide cost-effective real-time monitoring for forecasting; and expansion of weather stations can provide localized weather data for farmers;

-

Cultivate digital capabilities to manage climate risks. Strategic investments in “soft” infrastructure — digital climate services, advisory services, actionable information for producers, private-public partnerships for data production, and equal access to financial services — can all boost capacity to identify, manage, and respond to climate risks.