Highlights:

This edition of The State of Food and Agriculture focuses on the true cost of agrifood systems. By introducing the concept of the hidden costs and benefits of agrifood systems and providing a framework through which these can be assessed, this report aims to initiate a process that will better prepare decision-makers for actions to steer agrifood systems towards environmental, social and economic sustainability.

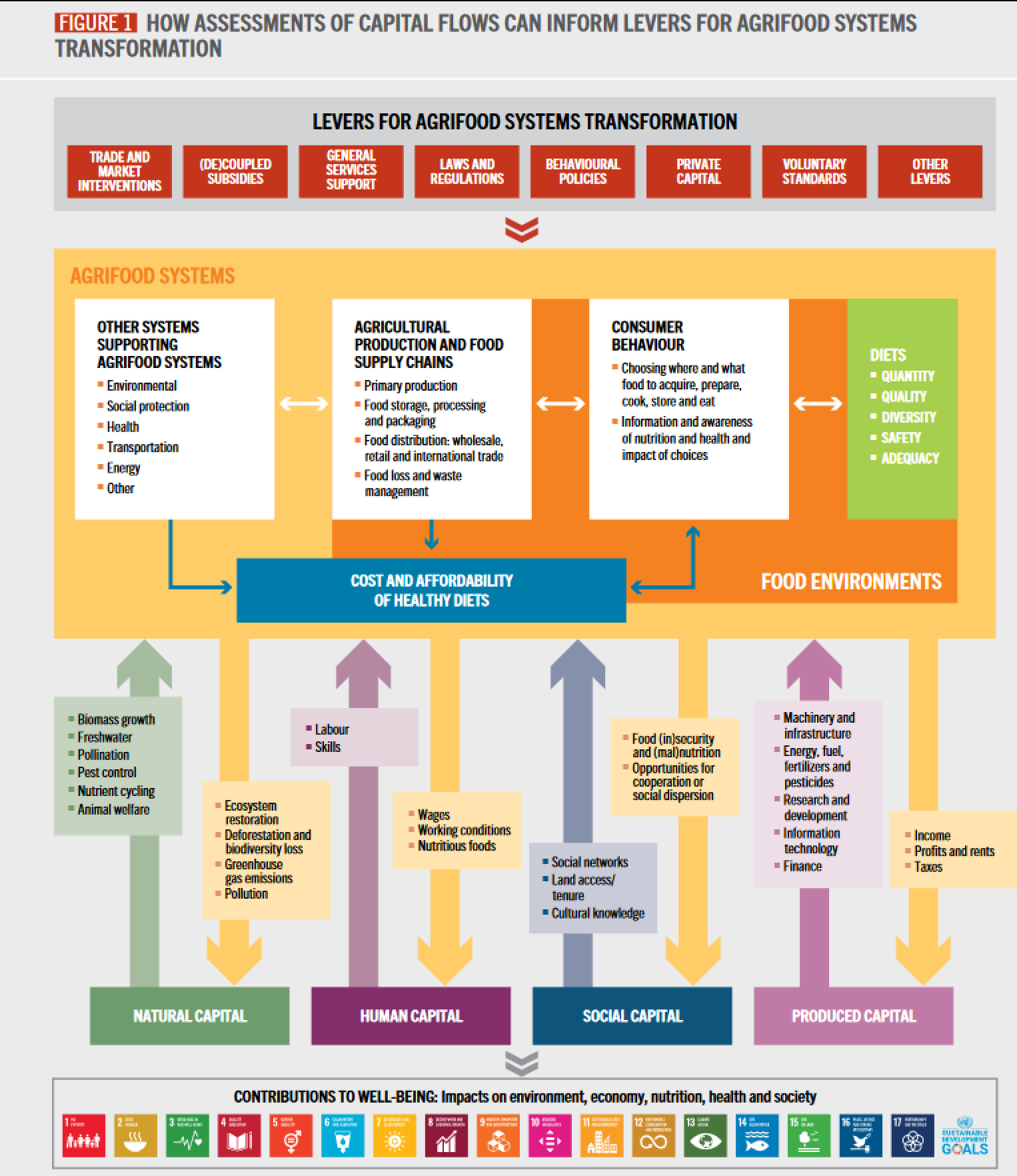

The true cost accounting (TCA) approach creates an unprecedented opportunity for such comprehensive assessments – it is defined as a holistic and systemic approach to measure and value the environmental, social, health and economic costs and benefits generated by agrifood systems to facilitate improved decisions by policymakers, businesses, farmers, investors and consumers.

This broad definition allows a variety of methods to be adopted, depending on a country’s resources, data, capacity and reporting systems. True cost accounting is also not a new concept. Rather, it is an evolved and improved approach that goes beyond market exchanges to account for all flows to and from agrifood systems, including those not captured by market transactions.

While the TCA approach is aspirational, as covering all hidden costs and benefits of agrifood systems is a massively resource- and data-intensive exercise, the aim is for policymakers and other stakeholders to avoid making decisions without a full assessment. In this regard, TCA enables decision-makers to pragmatically leverage already available data and information for an initial understanding of agrifood systems, including the most important data gaps, to better guide interventions.

Data that are commonly included in economic assessments pertain to the flows and impacts of produced capital and, to some extent, human capital (for example, labour and wages), which are transacted through market mechanisms and therefore easily observed, measured and quantified. Flows and impacts related to natural, social and (part of) human capital, in contrast, are not, so their inclusion in economic assessments is largely partial and not systematic. For example, while market-based inputs are directly reflected in the private production costs of producers, the inputs of ecosystem services (for example, clean freshwater and pollination) are not, despite being fundamental for agricultural productivity. However, when decision-makers lack a full assessment of the activities of agrifood systems causing impacts on capital stocks and flows – for example, relating to ecosystem services – the resulting knowledge gap can hinder progress towards more sustainable agrifood systems.

Negative impacts that are not reflected in the market price of a product or a service are referred to in this report as hidden costs.

The report proposes a two-phase assessment using TCA to provide decision-makers with a comprehensive understanding of agrifood systems and identify intervention areas to improve their sustainability. The first phase is to undertake initial national-level assessments that analyse and quantify as much as possible the hidden costs of agrifood systems across the different capitals (produced capital, human capital, social capital, and natural capital) using readily available data. The main role of the first phase is to raise awareness about the magnitude of the challenges. The second phase is devoted to in-depth assessments targeting specific components, value chains or sectors of agrifood systems to guide transformational policy actions and investments in a specific country.

PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF THE HIDDEN COSTS OF AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS FOR 154 COUNTRIES

For the first phase of the two-phase process, a preliminary TCA analysis was conducted for this report to quantify the hidden costs of agrifood systems for 154 countries. It uses national-level data (from various global datasets) to model impacts and combines these with monetary estimates to value (monetize) the hidden costs. This enables the results to be aggregated and compared on different dimensions and geographical scales and to be used as a foundation for dialogue with decision-makers. In this exercise, both hidden costs and benefits are factored in as much as possible, with hidden benefits (for example, afforestation) expressed as negative hidden costs.

However, because food holds intangible value – for example, in terms of the cultural identity associated with agrifood systems – some benefits cannot be monetized, so are excluded from the analysis, despite their importance. In addition, some hidden costs have been omitted due to data gaps across the set of countries being analysed, for example, costs associated with child stunting, pesticide exposure, land degradation, antimicrobial resistance and illness from unsafe food.

This report estimates that the global quantified hidden costs of agrifood systems were approximately 12.7 trillion 2020 PPP dollars in 2020. This includes environmental hidden costs from GHG and nitrogen emissions, water use, and land-use change; health hidden costs from losses in productivity due to unhealthy dietary patterns; and social hidden costs from poverty and productivity losses associated with undernourishment.

While not monetizing all benefits and costs is a limitation, it does not necessarily restrict the ability of the exercise to guide improvements in agrifood systems. Indeed, the hidden costs covered are more than sufficient to highlight the need for action. These estimates take into account the large uncertainty in cost calculations resulting from a lack of data on various hidden costs, as well as for some countries and regions, by using probability distributions. It is estimated that global hidden costs have a 95 percent chance of being 10.8 trillion 2020 PPP dollars or higher. Uncertainty was largest for environmental hidden costs, due to a lack of knowledge about the impact of nitrogen emissions on ecosystem services. Yet, even the lower bound reveals the undeniable urgency of agrifood systems transformation.

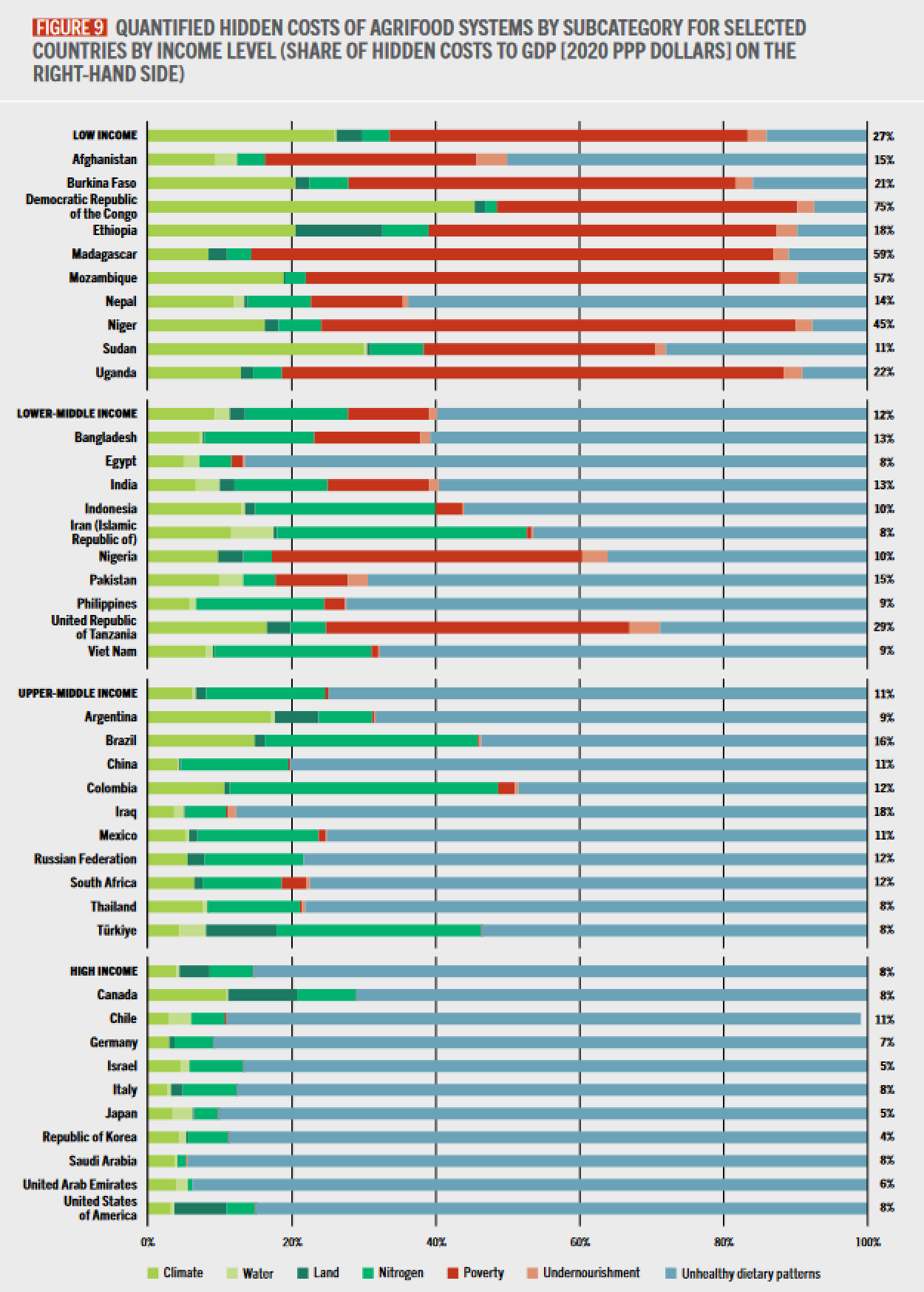

Aggregating the quantified hidden costs of agrifood systems at the global level hides significant variation across the income levels of countries that are key decision-makers in reducing these costs. The majority of hidden costs are generated in upper-middle-income countries (5 trillion 2020 PPP dollars, or 39 percent of total quantified hidden costs) and high-income countries (4.6 trillion 2020 PPP dollars, or 36 percent of total costs). Lower-middle-income countries account for 22 percent, while low-income countries make up 3 percent.

Hidden costs differ not only in their magnitude, but also in their composition by income level. In all country groups apart from low income, productivity losses from dietary patterns that lead to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the most significant contributor to agrifood systems damages, followed by environmental costs. In lower-middle-income countries, social hidden costs from poverty and undernourishment are relatively more significant, accounting for an average of 12 percent of all quantified hidden costs. Unsurprisingly, these social hidden costs are the main issue in low-income countries (more than 50 percent of all quantified hidden costs).

Globally, the quantified hidden costs are equivalent, on average, to almost 10 percent of 2020 GDP in PPP terms. However, this share is far higher in low-income countries, at an average of 27 percent. This signals that improving agrifood systems in low-income countries will be instrumental in addressing these hidden costs, especially those related to poverty and undernourishment, which alone are equivalent to 14 percent of GDP.

The hidden costs described are meant to help identify entry points for the prioritization of interventions and investments. In this respect, the first step should be to identify where in a given agrifood system hidden costs are more significant and due to what activities. Starting with the environmental dimension, estimates suggest that these costs occur mostly in primary production, with pre- and post-production costs comprising less than 2 percent of total quantified hidden costs. In other words, the primary sector should be seen as the main entry point for effecting change in environmental pathways. Globally, hidden costs from agriculture – through environmental pathways – are equivalent to almost one-third of agricultural value added.

For some countries the focus will likely be on the vulnerable actors and specifically on the contribution of agrifood systems to moderate poverty – that is, the overall distributional failure of sufficient revenues and calories needed to ensure productive lives. The report finds that, to avoid distributional failure costs in agrifood systems, the incomes of the moderately poor working in agrifood systems need to increase, on average, by 57 percent in low-income countries and 27 percent in lower-middle-income countries.

MOVING ON TO TARGETED TRUE COST ACCOUNTING ASSESSMENTS: THE SECOND PHASE OF A TWO-PHASE PROCESS

The objective of the second phase is to identify the potentially preferred transformational actions, comparing the costs and benefits of each – for example, through scenario analysis – in order to allocate resources to the most feasible and cost-effective ones, compare future options and manage trade-offs and synergies.

Scenario analysis is a critical feature of any TCA exercise, regardless of the boundaries of the analysis. Whether the domain of a TCA application is national agrifood systems, a local diet, a public investment or a value chain, scenario analysis allows the comparison of potential future paths and assesses the impact and effectiveness of different policies and management options. Doing so is essential for identifying emerging issues from inaction, as well as synergies and trade-offs from action.

Results of scenario analysis can be interpreted using cost–benefit analysis that compares the benefits and costs of different interventions and determines their economic and financial viability. Alternatively a cost-effectiveness approach compares the costs of meeting a given objective when using different intervention options, such as the cost per tonne of avoided emissions through energy efficiency, renewable energy and reduced deforestation. The latter approach is particularly relevant when considering options for reducing hidden costs of agrifood systems that have not been quantified in monetary terms.

True cost accounting can help nudge agrifood business and investment towards sustainability. By integrating TCA into everyday decision-making and management strategies, agrifood businesses can monitor and unlock opportunities at different stages of the supply chain, achieve sustainable production, attract private investment and avail of government incentives. When adopted by policy and backed by laws and regulations, TCA redefines key performance indicators and changes the bottom line of business success by including human, social and natural capitals. In brief, it redefines the concept of “successful business”. Financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies can also use TCA to determine credit and insurance conditions based on better risk assessments, thus improving credit and insurance conditions for sustainable businesses.

MAINSTREAMING TRUE COST ACCOUNTING FOR AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS TRANSFORMATION: OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

When based on TCA, levers can be used to improve agrifood systems sustainability. Levers can affect the supply side (production and intermediaries), the demand side (consumption) and public goods supporting agrifood systems.

No single lever is new, but the innovation lies in how they are used. When informed by targeted TCA assessments, existing levers in agrifood systems, such as agrifood subsidies, can be redirected or reformed to support and scale up promising and emerging strategies for sustainable businesses and investments.

A commonly asked question is whether addressing the hidden costs of agrifood systems will raise food prices. The basic premise is that it will depend on the hidden cost being addressed and the instruments being used. Considering the distinct categories of hidden costs being investigated is helpful: social hidden costs associated with distributional failures, which result in poverty and undernourishment; environmental hidden costs from damages linked to externalities; and health hidden costs due to dietary patterns that lead to obesity and NCDs. Addressing the social hidden costs from distributional failure, for instance, could improve productivity in the food and agriculture sector, exerting downward pressure on food prices, broadly benefiting consumers. Conversely, if producers are made to pay for measures (polluter pays principle) – for example, through taxes or regulations stipulating less environmentally harmful practices – not complemented by advice on how to limit costs where a hidden cost occurs, then these will be passed down the value chain or on to consumers in the form of higher food prices. Policies should not result in an increase in the price of food. One example is payment for environmental services, where the beneficiary pays the parties whose activities may be damaging to the environment to modify their behaviour.

One set of policies involving a mixture of the polluter pays principle and the beneficiary pays principle is the repurposing of agricultural subsidies. Shifting underperforming agricultural subsidies to protect and restore degraded farmland can better support local communities and help countries achieve their climate, biodiversity and rural development goals. If carefully designed and targeted, it also has the potential to increase the availability and the affordability of healthy diets, and in particular those that are environmentally sustainable. Targeted TCA assessments can inform the design of taxation and repurposing schemes to change relative food prices in favour of more nutritious and sustainable options.

Governments, with their policies, funds, investments, laws and regulations, play the central role in creating a conducive environment for the scaling up of TCA to transform agrifood systems. Research organizations and standard setters are also key for advancing methodologies and setting standards for data to be collected and used in TCA assessments. This is essential to guarantee the transparency of the true costs and benefits of agrifood systems. For this to happen on a large scale, especially in middle- and low-income countries, two major barriers must be overcome: data scarcity and lack of capacity.

| Year of publication | |

| Geographic coverage | Global |

| Originally published | 07 Nov 2023 |

| Related organisation(s) | FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| Knowledge service | Metadata | Global Food and Nutrition Security | Sustainable Food Systems | Food systems transformationHealthy diet |

| Digital Europa Thesaurus (DET) | policymakingpovertySustainable development goalscost analysisImpact Assessmentenvironmental impactpublic healthAid to agriculture |