There are two main problems with setting up an indicator dashboard to assess science systems. Firstly, some relatively straightforward technical issues: We often measure what is measurable, which isn’t necessarily the same as what is useful to know; and the potential for perverse incentives, or even just over-attention to what is measurable, is always a risk.

The second challenge is more existential. Does the science system have a goal? Visualising and mapping science systems perhaps inevitably gives the impression that the system was designed, and so can be controlled and adjusted, and operates towards a shared objective. None of this is true of evidence/policy systems, which tend to evolve organically. And members of this system have their own agendas and interests - not all researchers produce policy-relevant research, for instance. So, no – in itself, the system does not have a clear goal.

However, the JRC project is about supporting evidence use in policy. And the literature on evidence-informed policymaking does have a relatively shared understanding of what this means: deliverying relevant, robust evidence to people with the capacity to absorb and fully understand it in order that it might inform their decision-making. This is not a simple goal - big questions about what evidence is produced, what evidence counts for policy, how evidence and expertise reaches decision-makers, and how they can and do respond to this evidence all need to be considered; and all these questions have political, socio-technical and philosophical aspects.

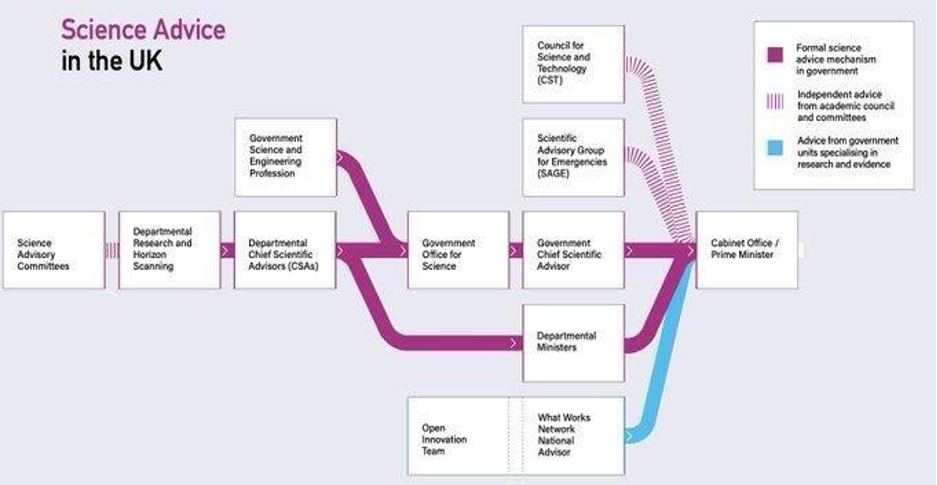

It is possible, though, to think about which types of organisations and individuals are involved in evidence production, mobilisation and use in decision-making; and to examine their connections and activities. In fact, we can start to think about the total set of actors and connections within the entire system through which scientific knowledge is acquired, synthesised, translated, presented for use, and applied in the policymaking process. This is my working definition of the science-for-policy system.

In the table below, I set out my preliminary thoughts about what these different groups might do in service of evidence-informed policymaking, and how we might know if they’re doing it (well). I am not yet sure, however, how these signs of activity might translate into measurable indicators.

|

Type of Actor |

Activities – what might they need to do? |

Possible indicators |

|

Funders

|

|

|

|

Research organisations |

|

|

|

Researchers |

|

|

|

Intermediaries |

|

|

|

Policymakers |

|

|

|

Parliament, media and other scrutiny bodies |

|

|

Although there are probably some missing groups, activities, and indicators, mapping these out shows at least three interesting things:

- Whether the groups and organisations involved agree on the goal of evidence-informed policymaking, or want to act in its service, all groups currently contribute towards this goal

- Mapping out the connections in this way offers potential points of intervention which could help improve the system's functioning

- However, interventions seeking to improve evidence use usually target one element or relationship, rather than at a systems level. This tends to add to a chaotic mass of activity, rather than improving systems functioning.

More thinking on these activities, goals, and indicators is needed, particularly around what we want our science-for-policy systems to do, for whom, and how.

Share this page

You can find Kathryn's…

You can find Kathryn's report following this link: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC129898. More information on our evaluation framework for institutional capacity of science-for-policy ecosystems are here: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/projects-activities/developing-ev…

Login (or register) to follow this conversation, and get a Public Profile to add a comment (see Help).

04 Jul 2022 | 08 Jul 2022