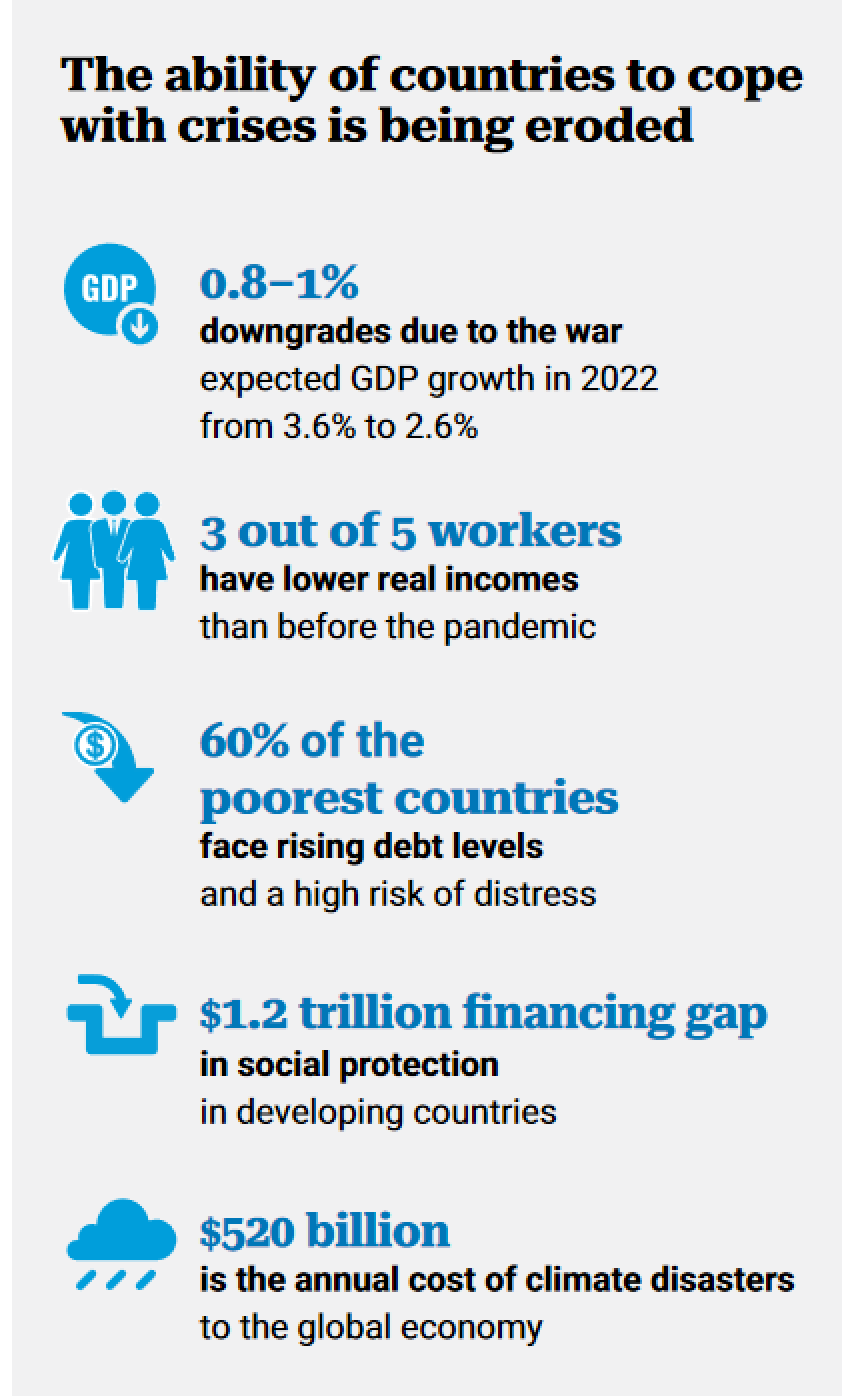

After two years of fighting COVID-19, the world economy has been left in a fragile state. Today, 60 per cent of workers have lower real incomes than before the pandemic; 60 per cent of the poorest countries are in debt distress or at high risk of it; developing countries miss $1.2 trillion per year to fill the social protection gap, and $4.3 trillion is needed per year - more money than ever before - to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The ability of countries and people to deal with adversity has therefore also been eroding. As the war erupted, global average growth prospects have been revised downward; many countries’ fiscal balances have deteriorated, and the average household has lost 1.5 per cent in real income due to price increases in corn and wheat alone. Worldwide, more people have been facing famine-like conditions, and more people have faced severe hunger emergencies. The lingering effects of the pandemic, coupled with the war in Ukraine and the impacts of climate change, are likely to further increase again the ranks of the poor. And as poverty increases so does vulnerability, particularly for women and girls.

Countries and people with limited capacity to cope are the most affected by the ongoing cost-of-living crisis. Three main transmission channels generate these effects: rising food prices, rising energy prices, and tightening financial conditions. Each of these elements can have important effects on its own, but they can also feed into each other creating vicious cycles - something that unfortunately is already starting. For instance, high fuel and fertilizer prices increase farmers’ production costs, which may result in higher food prices and lower farm yields. This can squeeze household finances, raise poverty, erode living standards, and fuel social instability. Higher prices then increase pressure to raise interest rates, which increase the cost of borrowing of developing countries while devaluing their currencies, thus making food and energy imports even more expensive, restarting the cycle.

In 2022, between 179 million and 181 million people are forecasted to be facing food crisis or worse conditions in 41 out of 53 countries where data are available. In addition 19 million more people are expected to face chronic undernourishment globally in 2023, if the reduction in food exports from the Russian Federation and Ukraine result in lower food availability worldwide. Record high food prices, exchange rate devaluation and inflationary pressures are key factors. While the FAO food price index had reached a record high in February 2022 before the war started, since then it has had some of the largest one-month increases in its history, with its record high in March 2022. And yet, despite a very challenging situation today, some factors suggest the food security situation may get much worse still in coming seasons.

Higher energy costs, trade restrictions and a loss of fertilizer supply from the Russian Federation and Belarus have led to fertilizer prices rising even faster than food prices. Many farmers, and especially smallholders, are thus squeezed to reduce production, as the fertilizers they need become more expensive than the grains they sell. Critically, new fertilizer plants take at least two years to become operational, meaning that most of the current supply of fertilizers is limited. Because of this key fertilizer issue, global food production in 2023 may not be able to meet rising demand. Rice, a major staple which up to now has low prices because of good supplies, and is the most consumed staple in the world, could be significantly affected by this phenomenon of declining fertilizer affordability for the next season.

Time is short to prevent a food crisis in 2023 in which we will have both a problem of food access and food availability. If the war continues and high prices of grain and fertilizers persist into the next planting season, food availability will be reduced at the worst possible time, and the present crisis in corn, wheat and vegetable oil could extend to other staples, affecting billions more people.

Export restrictions on food and fertilizers have surged since the start of the war. The scale of current restrictions has now surpassed that experienced during the food price crisis in 2007/08, which contributed to 40 per cent of the increase in agricultural prices. Trade restrictions today affect almost one fifth of total calories traded globally, which further aggravates the crisis.

The UN Global Crisis Response Group, together with the United Nations Regional Economic Commissions, undertook a global vulnerability assessment on the capacity of countries to cope with each of the channels of transmission and the vicious cycles they can create. The results confirm a widespread picture of vulnerability: 94 countries, home to around 1.6 billion people, are severely exposed to at least one dimension of the crisis and unable to cope with it. Out of the 1.6 billion, 1.2 billion or three quarters live in ‘perfect-storm’ countries, meaning countries that are severely exposed and vulnerable to all three dimensions of finance, food, and energy, simultaneously.

This vulnerability of Governments and people can take the form of squeezed national and household budgets which force them into difficult and painful trade-offs. If social protection systems and safety nets are not adequately extended, poor families in developing countries facing hunger may reduce health-related spending; children who temporarily left school due to COVID-19 may now be permanently out of the education system; or smallholder or micro-entrepreneurs may close shop due to higher energy bills. Meanwhile countries, unless a multilateral effort is undertaken to address potential liquidity pressures and increase fiscal space, will struggle to pay their food and energy bills while servicing their debt, and increase spending in social protection as needed.

The clock is ticking, but there is still time to act to contain the cost-of-living crisis and the human suffering it entails. Two broad and simultaneous approaches are needed:

1.Bring stability to global markets, reduce volatility and tackle the uncertainty of commodity prices and the rising cost of debt. There will be no effective solution to the food crisis without reintegrating Ukraine’s food production, as well as the food and fertilizer produced by the Russian Federation into world markets – despite the war.

2.Increase people and countries’ capacity to cope. This means helping the most severely exposed countries help their poor and vulnerable populations, by increasing countries’ fiscal space and liquidity access so that they can strengthen social protection systems and safety nets and hence enhance the ability of people to deal with adversity.

Taken together, this suggests – as the United Nations Secretary-General said recently – that “there is no answer to the cost-of-living crisis without an answer to the finance crisis”. All available rapid disbursement mechanisms at international finance institutions must be reactivated, and a new emission of Special Drawing Rights must be pursued. It is also important, however, to ensure resources are well spent. To complement efforts to create social protection systems, countries can respond to the crisis with additional targeted and/or, time-bound emergency measures, which should be aligned with sustainable development needs and not allocated universally. Lastly, a domino effect where solvency problems create a systemic developing country debt crisis must be avoided at all costs. The G7 and G20 need to rise to the challenge in putting forward debt restructuring instruments that are fit for purpose.

| Year of publication | |

| Geographic coverage | RussiaUkraineGlobal |

| Originally published | 27 Jun 2022 |

| Knowledge service | Metadata | Global Food and Nutrition Security | Food security and food crises | Food availabilityAccess to foodFood price crisisSafety netSmallholder farmer |

| Digital Europa Thesaurus (DET) | warcerealscrop productionagricultural tradetrade restrictionprice of energyfertiliserVulnerable groupssocial protectioncost of livingpolicymakingprice of agricultural produce |