Highlights:

In 2022, the demand for humanitarian assistance grew larger than ever. There was an exceptional donor response to the unprecedented increase in the number of people in need – driven largely by the war in Ukraine as well as worsening crises in Afghanistan and the Horn of Africa. Yet the scale of need meant the shortfall in humanitarian funding reached a record high. There is a growing number of complex, long-term crises. And the pressure placed on the humanitarian system to respond is only set to increase in 2023. This strain is being driven by continued system-wide shocks, including climate change and the war in Ukraine, and new and escalating crises, such as the devastating earthquakes in Türkiye and Syria and the worsening conflict in Sudan.

The imperative for significant change to humanitarian funding and response – and to better address the long-term root causes of, and recovery from, crises – is obvious and recognised but more pressing than ever. Ideas to address the humanitarian financing gap include establishing humanitarian funding targets to encourage more equitable burden sharing and repositioning the narrative around humanitarian assistance as an investment in resilience, to widen the donor base. Other proposals focus on the need to double-down efforts to reform the system, including the need to shift current business models to support greater local humanitarian leadership – for instance by identifying more effective local funding solutions such as locally managed global pooled funds.

Looking beyond humanitarian assistance, ideas for change reinforce the need to build the resilience of affected communities through long-term development strategies and mobilising funding for anticipatory action and additional climate finance, including through the new Loss and Damage Fund. Some proposals centre on the need to ensure access to flexible, multi-year funding, so that local organisations can increase preparedness to shocks and respond flexibly to the needs of their communities while maintaining a focus on building capacities to mitigate impacts of future crises.

This summary of the Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2023 presents key findings about:

-

Trends in humanitarian need and crisis in 2022

-

Trends in humanitarian funding

-

Progress made on commitments to a better humanitarian system, with a focus on locally led action

-

How resources beyond humanitarian funding – such as climate finance – could be used to address cycles of crises

A third more people were in need of humanitarian assistance in 2022, with most facing long-term crisis.

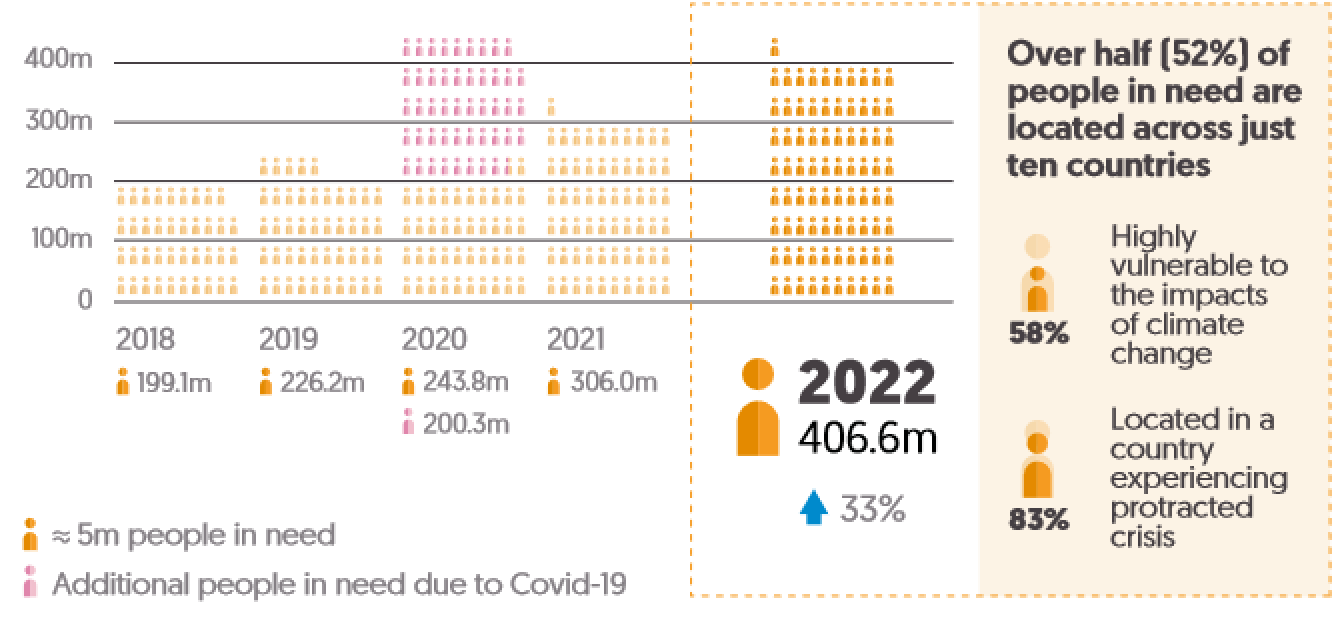

In 2022 alone, 406.6 million people were in need of humanitarian assistance. Data on gender and age is available for just a third of UN-coordinated appeals. But where this data exists it shows that half of people in need are children under the age of 18 (49%, or 90 million). Several large-scale protracted crises account for the bulk of humanitarian needs, with more than half of all people in need over the past five years living in just 10 countries.

A growing number of people in need face intersecting threats from conflict, climate change and socioeconomic vulnerability. In 2022, three-quarters of all people in need of humanitarian assistance faced at least two risk dimensions: conflict, climate and/or socioeconomic vulnerability. This means that most crises are now long-term; a growing majority of people in need (83%) live in a country that has had a UN-coordinated appeal for five or more consecutive years.

One of the primary drivers of need in 2022 was food insecurity; the number of people experiencing severe food insecurity continued to grow, driven by the war in Ukraine and a food crisis in the Horn of Africa. An estimated 265.7 million people were facing crisis-level acute food insecurity in 2022/23. This is more than double the number of people (115.2 million people) facing this level of food insecurity in 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic. The severity of food insecurity – as well as the number of people experiencing it – should inform how responses are targeted. These two factors do not always correlate. In Somalia, the number of people affected rose from 2.6 to 8.3 million, and the severity of food insecurity increased more than in any other country. However, in Pakistan, where a similar rise in the number of people experiencing food insecurity (from 2.7 to 8.6 million) occurred, there was a significant decrease in the severity of food insecurity.

Forced displacement also continued to drive rising levels of humanitarian need. An additional 16.5 million people were displaced internally or across borders in 2022; over 10 million of these were people affected by the war in Ukraine.

Both public and private donors gave substantially more humanitarian funding in 2022. Total international humanitarian assistance (from public and private donors) increased by US$10.0 billion (27%) to US$46.9 billion. The increase in funding was in response to appeal requirements in 2022 that stood at a record US$52.4 billion, an increase of 37% from 2021. This was driven in part by the significant jump in funding requested through the Ukraine, Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Somalia appeals. At the time of writing, requirements for 2023 have already eclipsed this, with a total US$54.9 billion requested to meet new and worsening crises. Despite the unprecedented response, driven partly by strong donor solidarity with Ukraine, the appeals funding shortfall grew to a record US$22.1 billion in 2022.

10 countries received almost two-thirds of all funding, with Ukraine receiving the largest ever volume in one year. The largest recipient of humanitarian funding in 2022 was Ukraine – receiving the highest volume of contributions ever recorded in one year (US$4.4 billion). As in previous years, a small number of large long-term crises absorbed the majority of funding – in 2022, the 10 largest recipients of humanitarian assistance received 63% of total country-allocable funding. In addition to Ukraine, four countries (Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria and Ethiopia) received more than US$2 billion each in humanitarian funding.

The volume and share of funding provided to UN agencies increased in 2022. In the context of rapidly growing requirements and limited resources, the need to ensure that humanitarian assistance is delivered as effectively and efficiently as possible is more urgent than ever. UN agencies continued to receive the majority of funding from public donors. In 2022, the share of funding they received grew from 52% in 2021 to 61% (US$22.8 billion). Despite calls for better reporting, generally there is inadequate data on how this funding is passed on.

Local and national actors continue to receive minimal funding directly from donors. Progress against commitments to support greater local humanitarian leadership through increasing funding to local and national actors has been disappointing. There was no increase in the proportion of total international humanitarian assistance provided directly to local and national actors in 2022, which stood at just 1.2% (US$485 million).

The steady growth seen since 2017 in the provision of humanitarian assistance as cash and vouchers continued in 2022. The use of cash and vouchers rose in response to the Ukraine conflict and rising levels of food insecurity, increasing by a record 40% to US$7.9 billion in 2022. Cash and vouchers accounted for an estimated 20% of total humanitarian assistance in 2022.

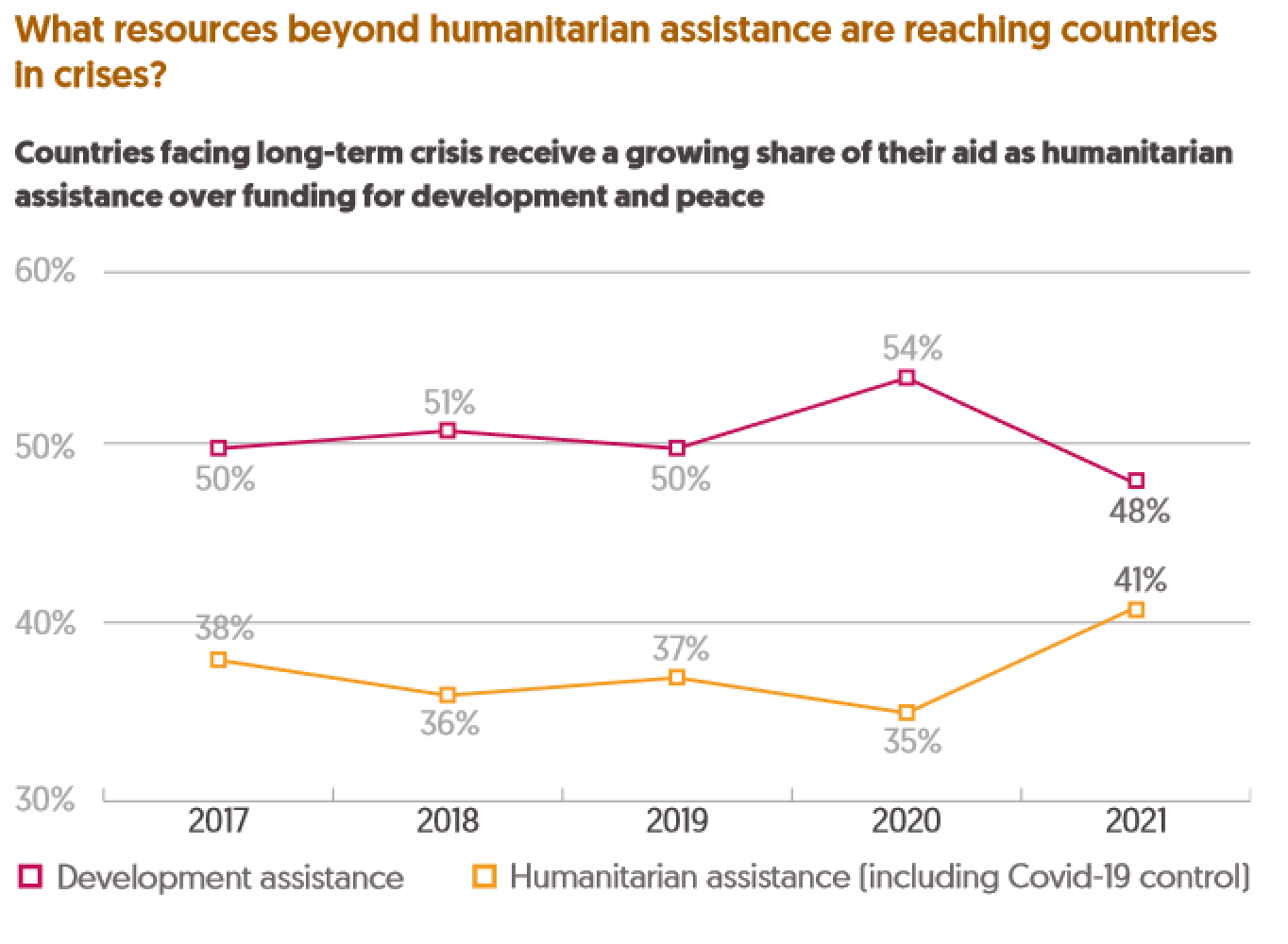

Countries facing humanitarian crisis are also recipients of development, peace and climate financing. Countries facing long-term crisis have not seen a notable transition from humanitarian to longer-term development assistance.

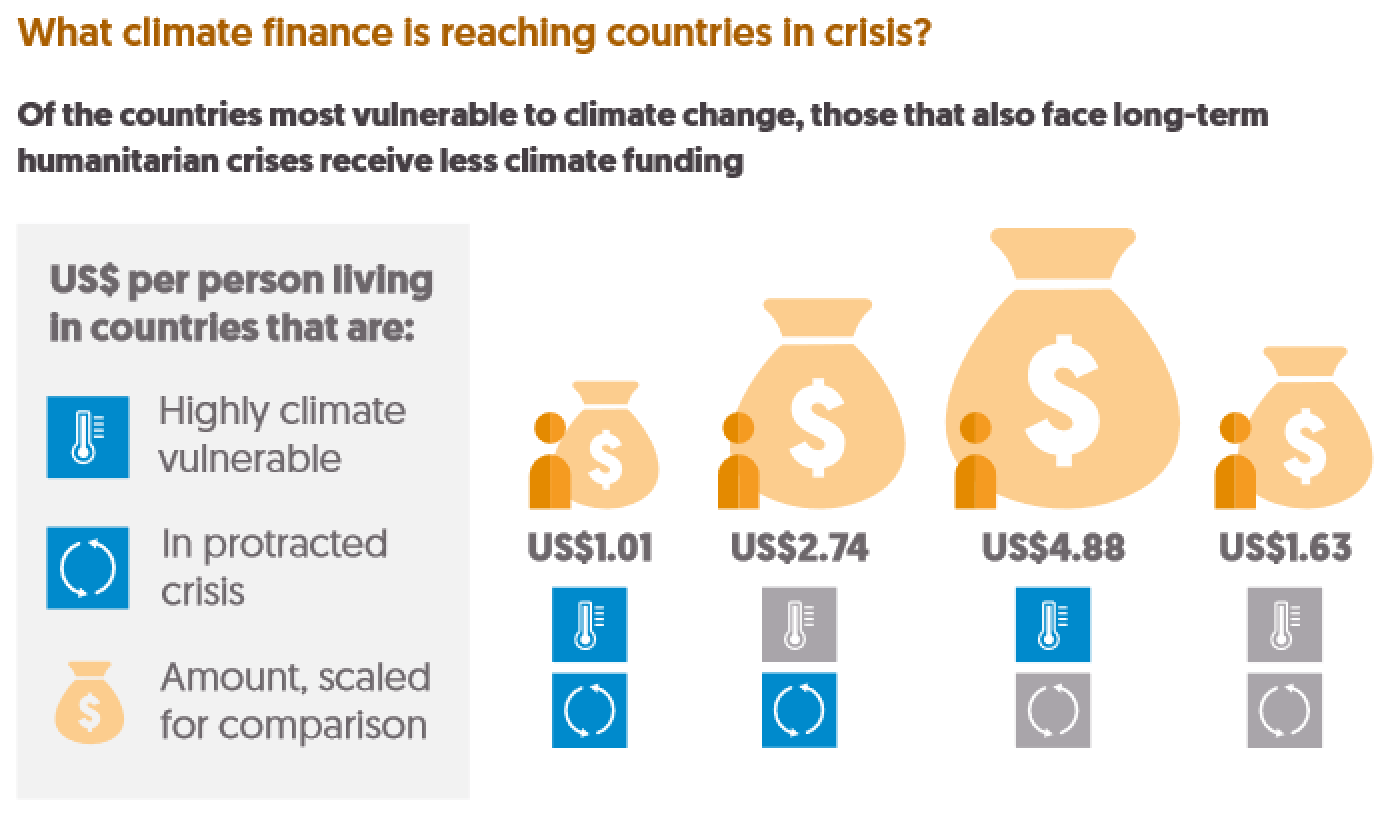

The accelerating impacts of climate change are driving new crises and compounding existing risks. Funding requirements linked to extreme weather are as much as eight times higher than they were 20 years ago. Despite this, countries that are most vulnerable to climate-related shocks are not receiving the necessary funding to prepare for and alleviate these shocks. People in countries experiencing protracted crisis and a high level of climate vulnerability receive a lower proportion of their total ODA as climate finance than other climate-vulnerable countries. They also receive less finance from multilateral climate funding mechanisms and less per capita multilateral climate finance: US$1 per person, compared to US$4.88 per person in the most climate-vulnerable countries not experiencing long-term crisis.

| Year of publication | |

| Publisher | Development Initiatives |

| Geographic coverage | PakistanYemenSomaliaSyriaAfghanistanEthiopiaGlobal |

| Originally published | 22 Nov 2023 |

| Knowledge service | Metadata | Global Food and Nutrition Security | Food security and food crises |

| Digital Europa Thesaurus (DET) | humanitarian aidclimate changeaid evaluationwar in Ukraine |