The first half of 2022 has witnessed one of the largest shocks to global food and energy markets that the world has seen in decades. As economies rebounded from the COVID-19 pandemic, sluggish supply chains struggled to keep up with increasing demand for food and energy, leading to supply bottlenecks that resulted in upward pressure on prices. The war in Ukraine has exacerbated these trends. Trade restrictions arising from concerns about food and energy security have led to major price spikes. Compounding these challenges, increased hydrological uncertainty and extreme weather events have reduced harvests and energy production in many parts of the world, adding to market volatility and uncertainty.

While most countries are impacted by these price shocks, poor households are more vulnerable to adverse shocks in the short term. Currently, 2022 is forecast to be the second-worst year for poverty reduction in decades. It is estimated that around 100 million more people are expected to be in poverty as a result of the combined impacts of COVID-19 and inflation. Protecting poor and vulnerable households, across countries at all income levels, is a top priority.

Food and energy sectors, while distinct, are linked in several ways. Natural gas is used both as a feedstock and energy source in the production of ammonia (a base material for nitrogen fertilizer), accounting for 70- ì 80 percent of ammonia production costs. The rapid increase in gas prices has turned into an increase in fertilizer prices. Hence, the food crisis has spread from food importers to producers, with at least 89 countries importing more than 90 percent of their nitrogen-based fertilizers. In addition, as land and certain food commodities (e.g., corn) are diverted towards energy use (4 percent of global agricultural land is currently devoted to producing biofuels), some countries face a difficult choice between securing food or energy supplies. These impacts are compounded by rising prices of petroleum products needed to support harvesting, transporting, and processing of food. The food-energy-water nexus brings additional challenges in an increasingly water stressed world.

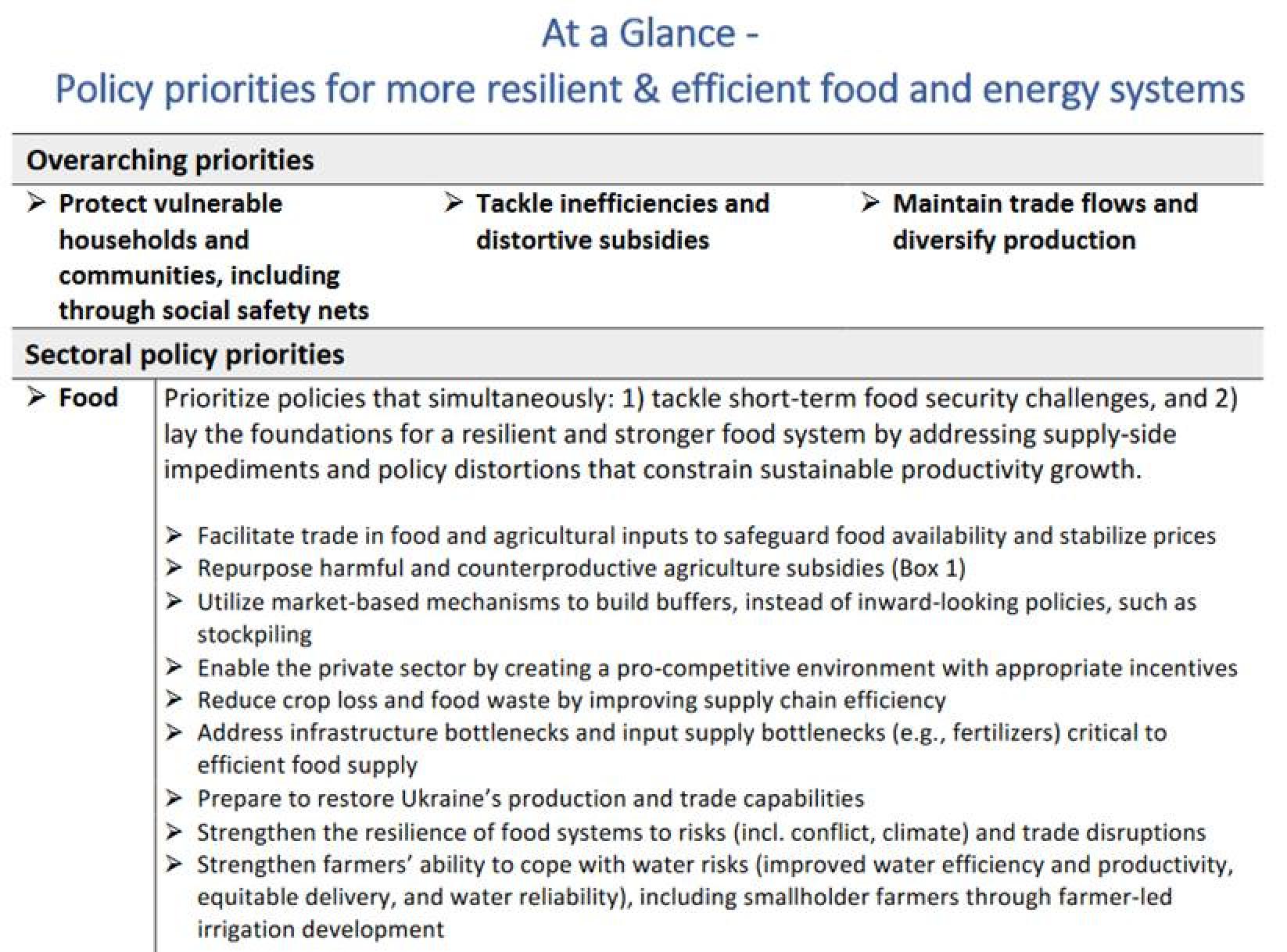

In the face of these challenges, countries can tackle the food and energy price crises in ways that contribute to efficiency, shared prosperity, and sustainability. This will require focusing on three main objectives:

-

Protecting vulnerable households and communities: Nutrition-sensitive social safety net systems are an urgent and immediate priority. While the COVID-19 crisis has already triggered an unprecedented scale-up in social safety nets, these must be targeted to ensure the affordability of essential foods and energy for vulnerable populations, especially female-headed households that are often disproportionally poorer.

-

Tackling inefficiencies and distortive subsidies: There is scope to improve the efficiency of both production and consumption in food and energy value chains alike. Globally, governments spend enormous amounts on subsidies that can engender systemic inefficiencies – around US$635 billion in the agriculture sector, and US$577 billion for fossil fuel subsidies. These funds, which total around US$1.2 trillion, could be repurposed towards more productive uses - such as investments in resource use efficiency, renewable energy, health, education, and targeted cash transfer programs.

-

Maintaining trade flows and diversifying production: Trade restrictions are counterproductive and exacerbate supply problems. By facilitating regional integration and trade in food, agricultural inputs, and electricity, countries can increase efficiency and resilience of supply. Supporting trade finance and agribusiness are important levers for accomplishing this. Freer trade offers greater opportunities for private sector participation. In the longer term, expanding and diversifying production into markets that have the appropriate comparative advantages can strengthen resilience to disruptions.

| Year of publication | |

| Geographic coverage | Global |

| Originally published | 19 Dec 2022 |

| Related organisation(s) | World Bank |

| Knowledge service | Metadata | Global Food and Nutrition Security | Food security and food crises | Food crisisFood price crisis |

| Digital Europa Thesaurus (DET) | price of energywar in UkrainefertiliserinflationhouseholdCrisispolicymakingImpact Assessmentaid systemcrisis management |