Context:

The 2023 Global Report on Food Crises revealed that in 2022, nearly 258 million people in 58 countries and territories were in Crisis or worse acute food insecurity (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification [IPC]/Cadre Harmonisé [CH] Phase 3 or above, or the equivalent) – up from 193 million in 53 countries and territories in 2021. This represents the highest on record since the Global Report on Food Crises started reporting these data in 2016, even while considering an increase in the population analysed. These food crises are the result of interconnected, mutually reinforcing drivers – conflict and insecurity, economic shocks and weather extremes, as well as structural vulnerabilities – such as poverty, fragile agrifood systems and rural marginalization. In 2022, these key drivers were associated with lingering socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19, the knock-on effects of the war in Ukraine and repeated droughts and other weather extremes.

Against this background, the Financing Flows and Food Crises report serves as a companion piece to the Global Report on Food Crises by providing an evidence- based snapshot of humanitarian and development financing trends to food sectors in food crisis contexts. A better understanding of external financing trends is essential to inform decision-making and promote policy dialogues to ensure improved coherence and coordination among partners. While humanitarian assistance remains critical to providing rapid support to save lives and livelihoods, and alleviate human suffering, more coordinated efforts are needed to address the root causes of food crises that could ultimately reduce the need for humanitarian assistance.

Key findings:

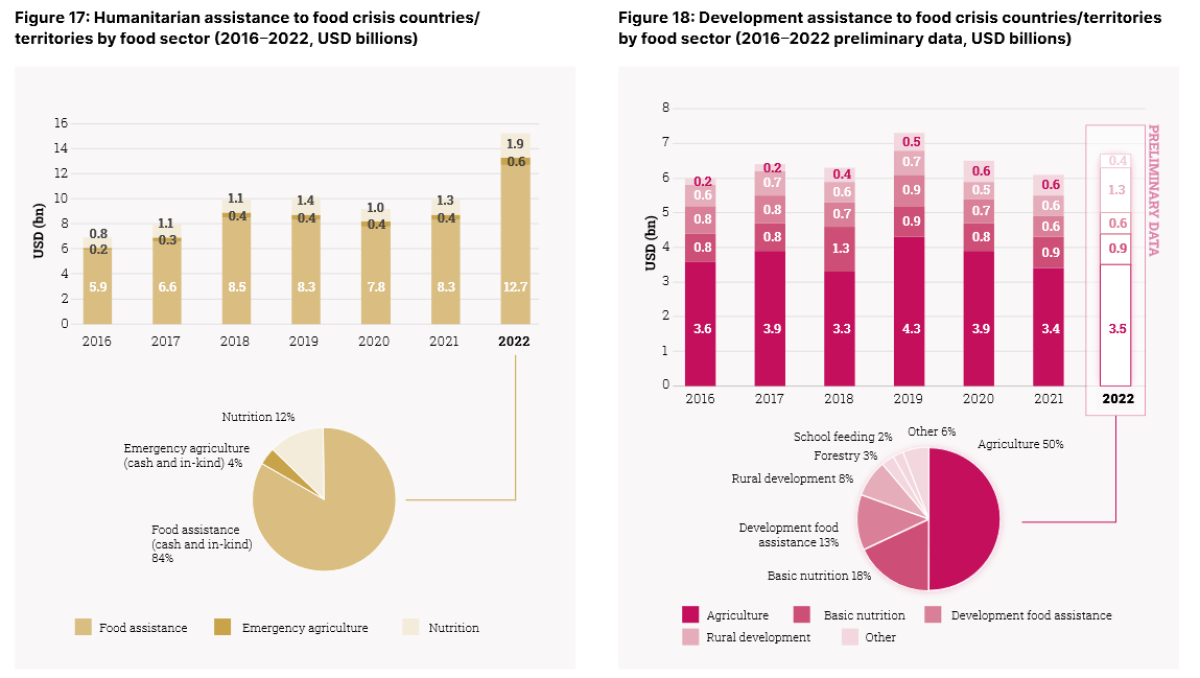

1. The report highlights that the financing of food sectors in food crisis contexts is not successfully tackling acute food insecurity. The current trends in external financing fail to pave the way for sustainable improvements in food security. While 2022 saw a seven-year high in allocations to food sectors in food crisis countries and territories, acute food insecurity levels peaked in 2022, with an all-time high of 258 million people facing Crisis or worse conditions (IPC/CH Phase 3 or above or equivalent) in a total of 58 countries and territories. Furthermore, it is expected that the 2022 record levels of humanitarian financing will not be sustained and a decrease is expected in 2023. Humanitarian financing witnessed a significant increase of 52 percent from 2021, peaking at over USD 15 billion in 2022. Yet acute food insecurity continued to escalate due to consistently high numbers of people affected in some contexts, worsening situations in others, as well as increased analysis. Meanwhile, development assistance to food sectors remained stagnant at around USD 7 billion per year.

2. Allocations to food sectors in food crisis contexts for humanitarian and development assistance remains marginal when situated against global external financing. Global development financing tends to be more than six times higher than its humanitarian counterpart, and while a significant amount of it is directed to food crisis contexts, just 3 percent goes to food sectors in these countries and territories, compared to 32 percent of global humanitarian financing. This implies that the financing of food sectors in food crisis contexts remains part of a predominantly humanitarian portfolio, even if food crises are more and more protracted in nature, having lasted over seven years.

3. Humanitarian funding allocations continued to be highly concentrated in regions with the highest acute food insecurity needs. In 2022, the ten largest recipients of humanitarian allocations included some of the largest food crises in the world and absorbed almost 71 percent of all humanitarian allocations to food sectors in food crisis contexts. In terms of development financing, the ten largest recipients are all countries facing protracted food crises and absorbed 46 percent of all development financing. Moreover, the record high of humanitarian funding in 2022 was primarily driven by just seven countries, while development assistance saw a more balanced increase from 2021 to 2022.

4. Although there has been a significant increase in humanitarian financing in 2022, the proportion allocated to emergency agriculture interventions remained largely unchanged. Zooming in how these allocations to food sectors in food crisis contexts are disbursed, just agriculture interventions. This is in spite of the sector being the main source of food and income for at least two-thirds of those experiencing high acute food insecurity. While development allocations to agriculture are better represented in these contexts, they still represent on average just 57 percent of the 3 percent of global development funding4 percent of this humanitarian financing is directed to emergency.

5. Long-term investments should create an enabling environment for sustainable development in food crisis contexts, so that humanitarian assistance can effectively respond to immediate needs without being overstretched in addressing protracted emergencies. This would allow for an appropriate layering and sequencing between humanitarian and development financing to address the root causes of acute food insecurity and reduce humanitarian needs. Particularly in countries with protracted crises and recurrent famine-risk contexts, where humanitarian assistance prevails as the primary source of food sector funding and development financing remains marginal, greater coherence is essential to build stability and prevent severe food insecurity outcomes in the future.

| Year of publication | |

| Publisher | Global Network against Food Crises (GNAFC) |

| Geographic coverage | Global |

| Originally published | 19 Feb 2024 |

| Knowledge service | Metadata | Global Food and Nutrition Security | Food security and food crisesClimate extremes and food security Nutrition | Extreme weather eventCountries affected by conflictFood price crisis |

| Digital Europa Thesaurus (DET) | humanitarian aidAid to agricultureaid systemaid policycrisis managementwar in Ukraine |