The use of scientific evidence in policymaking and practice is widely believed to produce better decisions and more sustainable outcomes. In this blogpost, Benjamin Hofmann and Karin Ingold outline important barriers to evidence use and their roots in actors’ motivations. Based on a study with colleagues from five Swiss research institutions, they illustrate these barriers for pesticide risk reduction in agriculture.

Sustainability challenges, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and chemical pollution, are in the spotlight of policymaking in many countries. To tackle these complex challenges, it is common to call for more and better research. The actual impact of science, however, depends on whether and how decision-makers use the evidence that scientists generate. In an article published in the journal Ambio, our project consortium identifies barriers to evidence-informed decisions in policy and practice and outlines measures to overcome them. Our recommendations can inform efforts to enhance the use of science in policymaking, including the debate that has been unfolding within the EU following the release of the Commission Staff Working Document on “Supporting and connecting policymaking in the Member States with scientific research”.

Three actor motivations in evidence use

In our study, we develop three ideal-typical models of how actors deal with scientific evidence. Actors are individuals or organizations that assume political roles (e.g., parliamentarian or interest group) or are part of value chains (e.g., input suppliers, producers, retailers, consumers). Our models consider that actors may have different motivations:

I. Truth-seekers take decisions based on the best available evidence. For these actors, supply of more and better scientific evidence is essential for reaching decisions that deliver more sustainable outcomes.

II. Sense-makers seek to marry new scientific evidence with their prior beliefs. For these actors, evidence supply and demand need to match. For instance, scientific evidence needs to resonate with their experiences and provide feasible solutions to sustainability challenges.

III. Benefit-maximizers use scientific evidence strategically to advocate predefined interests in policy and practice. Strategic demand of these actors determines which evidence is used (or even generated) to support or block sustainable transformation.

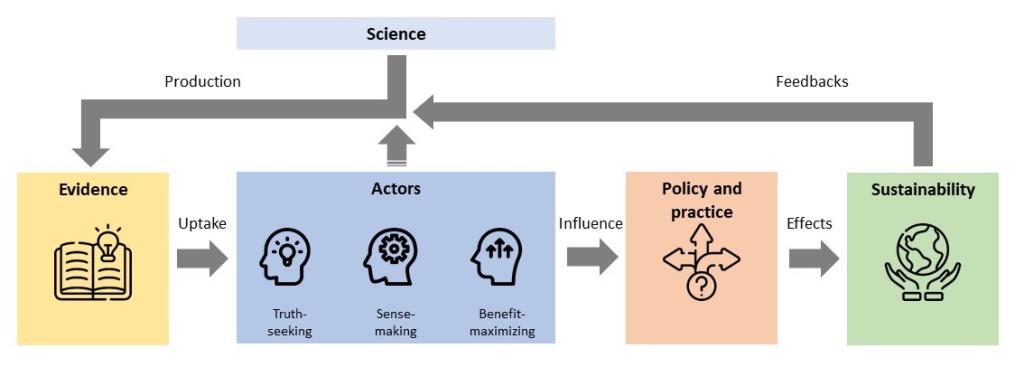

Framework: actors with different motivations shape the stages of evidence use for sustainable policy and practice (figure: Benjamin Hofmann, icons from Freepik at https://www.flaticon.com/authors/freepik).

We assess these actor models in all stages of evidence use, including (1) scientific evidence production, (2) evidence uptake by actors, (3) influence of evidence on policy and practice decisions, (4) sustainability outcomes of evidence-informed policies and practices, and (5) evidence feedbacks based on impact evaluations. This framework allows for a comprehensive assessment of barriers to evidence use for sustainability.

Barriers to evidence use for pesticide risk reduction

We applied our framework to the reduction of risks posed by pesticide use in agriculture. Sustainable plant protection is a complex challenge linked to several UN Sustainable Development Goals (e.g., food security, good health, clean water, and protection of life on land). In the Farm-to-Fork Strategy, which forms part of the European Green Deal, the European Commission has proposed a 50% reduction of chemical pesticide use and risks by 2030. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework adopted in December 2022 sets a similar on the global level. However, plans to cut pesticide risks continue to be highly controversial in the EU and abroad with scientific evidence being used or disputed to support certain policy and practice options and to block others. In our study, we synthesize the state of research on the role of evidence in pesticide policy and practice combining insights from health and environmental sciences, agricultural economics, agronomy, political science, and decision analysis.

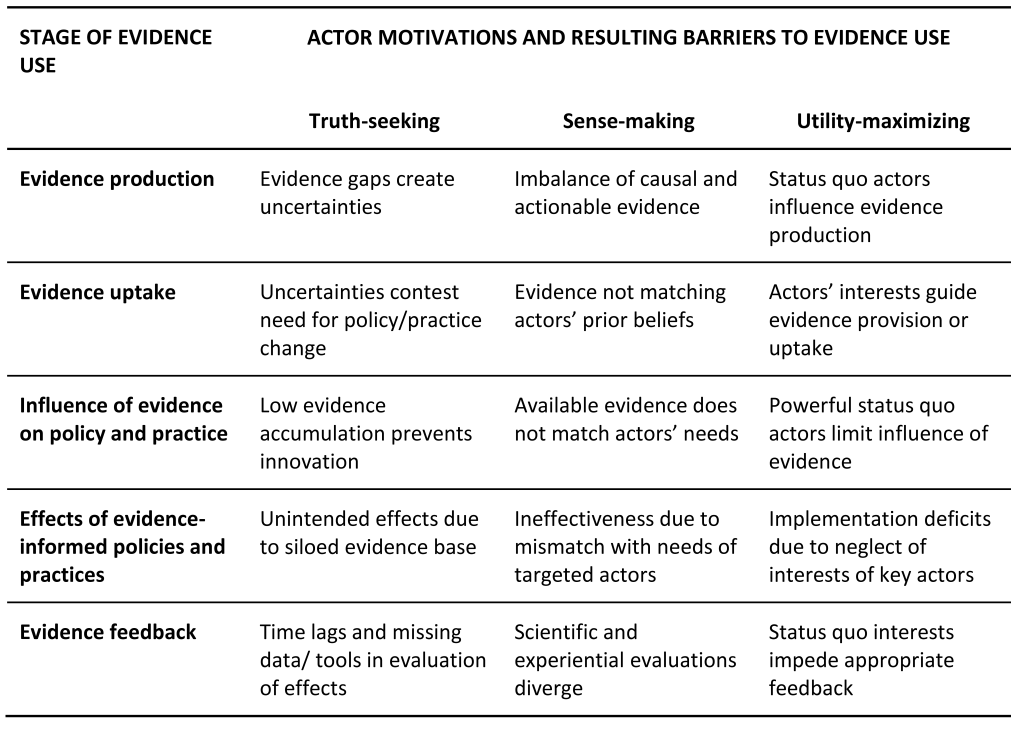

Our synthesis identifies typical barriers to evidence-informed pesticide policy and practice resulting from diverse actor motivations in different stages of evidence use (see table below). Examples are:

I. Truth-seekers can draw on comprehensive scientific evidence about the environmental and human health impacts of pesticides that justify risk reduction measures. However, they also have to deal with remaining uncertainties in evidence production, for instance, regarding causal relationships between the use of certain pesticides and chronic human diseases.

II. Sense-makers integrate those pieces of evidence in their decision-making that can be reconciled with their prior beliefs and knowledge. For example, studies have shown that the decision of farmers to reduce pesticide use depends, amongst others, on their knowledge of sustainable farming practices and of success stories from other farmers.

III. Benefit-maximizers with their interests influence which evidence is considered in decisions and which impact these decisions unfold. An example from the literature is that farmers advised by private services are more likely to use synthetic insecticides than those advised by public services

Possible barriers to evidence-informed policy and practice for sustainability (table from original study).

Recommendations to overcome barriers to evidence use

Based on this overview, we propose three sets of measures to increase the use of scientific evidence in policymaking and practice:

I. Where evidence gaps hamper truth-seekers, the generation and accumulation of evidence needs improvement. Suitable measures include more interdisciplinary collaboration, global-local knowledge integration, faster evidence syntheses, and more financial resources for clearly defined impact evaluations as a source for evidence feedbacks.

II. For sense-makers, transdisciplinary knowledge coproduction among actors from science, policy, and practice can increase the match of evidence supply and demand. Additional elements are the strengthening of organizations brokering knowledge to different actors and more support for solution-oriented research.

III. Regarding benefit-maximizers, transparency requirements can limit the strategic or even improper use of evidence. Publication of all data collected with public money can prevent private data monopolies. Additionally, a mandatory evidence documentation for important political decisions can render the use of evidence traceable.

In reality, the co-occurrence of all three types of actors calls for a mix of these measures to improve evidence use in policy and practice. The need for a mix of measures also becomes apparent in the Commission Staff Working Document, which summarizes a broad set of existing science-for-policy instruments. Our recommendations highlight how to strengthen these instruments further.

Authors

Benjamin Hofmann (benjamin.hofmann@eawag.ch) is a postdoctoral researcher in the Environmental Social Sciences Department at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology.

Karin Ingold (karin.ingold@unibe.ch) is Professor of Policy Studies and Environmental Governance at the Institute of Political Science of the University of Bern, Vice-president of the Oeschger Center for climate change research, and research group leader at the Environmental Social Sciences Department at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology.

Original study (open access)

Hofmann, B., Ingold, K., Stamm, C. et al. Barriers to evidence use for sustainability: Insights from pesticide policy and practice. Ambio 52, 425–439 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-022-01790-4

Acknowledgements

This blogpost is based on a longer post that we co-authored with Robert Finger, Christian Stamm, and Sabine Hoffmann and that was published in German at the Agrarpolitik-Blog. The original study and the blogposts are part of the Sinergia project TRAPEGO («Evidence-based Transformation of Pesticide Governance») funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (https://trapego.ch, No. CRSII5_193762). We thank all co-authors of the original study.

Share this page

Login (or register) to follow this conversation, and get a Public Profile to add a comment (see Help).

30 Jan 2023