Highlights:

Part 1.3 deals with adaptation and greater resilience to climate change.

Chapter 1.3.1 deals specifically with the challenges linked to agriculture.

It shows that Kenya’s agriculture and pastoral systems are highly vulnerable to climate change.

According to the authors, Climate impacts on agriculture and productivity of specific crops are expected to vary, based on the climate change scenario (figure 1.5).

For some key export crops, such as coffee and beans, the production shock is predominantly negative compared to the baseline. The same is true for some key food security products, such as maize and cassava, while for others, the spread of the production shock (including the means) is quite large compared to the baseline.

But in aggregate, the impact of the mean of different clusters of climate projections results in a decline in the contribution of agriculture value add to overall GDP, if no action is taken.

Without intervention, the projected annual variability in precipitation could compromise food security and Kenya’s agricultural export basket. Recent weather shocks (five consecutive seasons of drought) have already resulted in 14 counties being classified as having at least acute food insecurity. Maize is the staple cereal, synonymous with food and nutrition security. Improving maize production and storage systems could boost levels of productivity and reduce postharvest losses, bolstering resilience to shocks.

To buffer the impact of climate on Kenya’s export basket, which largely comprises primary agricultural products, the agrifood sector could diversify exports and adding value to several commodities, including milk, chocolate, prepared or preserved meats, cheese, and wood and paper-based products.

Flooding is responsible for most of the additional costs, followed by precipitation and temperature change.

Part 3 advises on measures for inclusive growth that increase climate resilience and maintain a low carbon path.

Chapter 3.1. deals more specifically with managing water, land and forests for climate-resilient agriculture and rural economies.

According to the authors, integrating climate considerations into the implementation of Kenya’s Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy (ASTGS) 2019–29 can increase resilience and productivity in the sector.

In particular, expanding investment in agricultural research and technology dissemination will be central for increasing productivity while mitigating GHG emissions from the agriculture sector.

Sustainable mechanization, as part of efforts to scale out climate-smart agriculture (CSA), will be instrumental on two fronts: improving agricultural labor productivity and sustainably managing soils and water to maximize output.

If it wants to expand agriculture in a sustainable manner, Kenya will need to tackle the land constraint.

To improve agricultural productivity and value added, Kenya will need to crowd in private sector funding and improve capital infrastructure.

To deliver on the ASTGS in a climate-informed manner, Kenya will need to restructure institutional arrangements, increase public expenditure in the sector, and reduce government intervention in output markets.

Part 4 of the report deals with Climate change impacts on growth.

Chapter 4.3 deals with the poverty impacts of climate change shocks.

It shows that not acting to address climate change will set back Kenya’s poverty reduction gains and increase inequality.

When we consider climate change impacts, the gains in reducing poverty are set back, and in a dry/hot climate future scenario under BAU, there are 1.1 million additional poor in 2050. Under ASP, the poverty headcount increases by 25,000 in a dry/hot climate future scenario compared to the baseline. These results are largely explained by the impact of climate on agricultural production and labor. Without climate change, the Gini coefficient is predicted to increase from 40.7 in 2021 to 43.5 in 2050. Under BAU, both climate scenarios result in an increase in the Gini coefficient relative to the baseline. The trend is similar under ASP growth, but the deviation is much smaller.

Part 5 deals with prioritizing action and mobilizing climate finance.

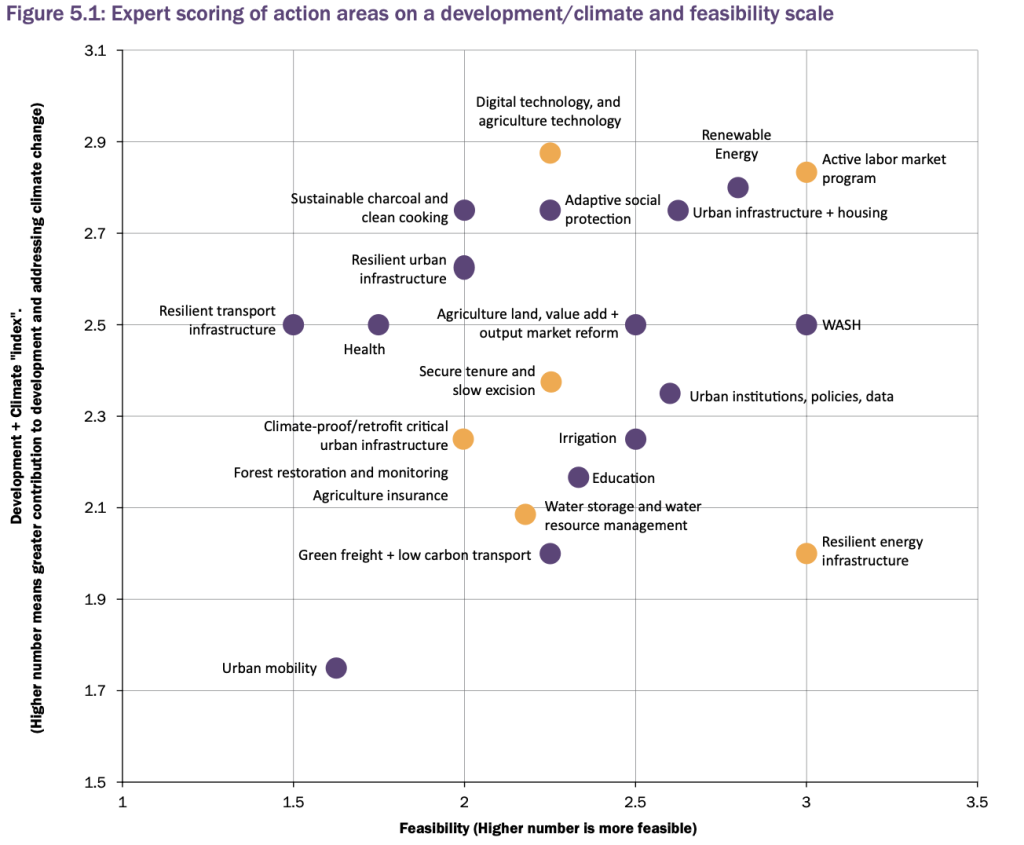

A graphical representation of an aggregation of the expert ranking (figure 5.1) reveals which actions are more feasible and have positive climate and development impacts.

The expert ranking shows that actions related to urban resilience, and development actions that contribute to the resilience of human capital (social protection, active labor market policies, health, WASH, and education), the productivity of agricultural systems (agricultural technology, secure tenure, forest restoration and monitoring, agricultural insurance, and value addition and output market reform), and renewable energy can result in climate-positive development.

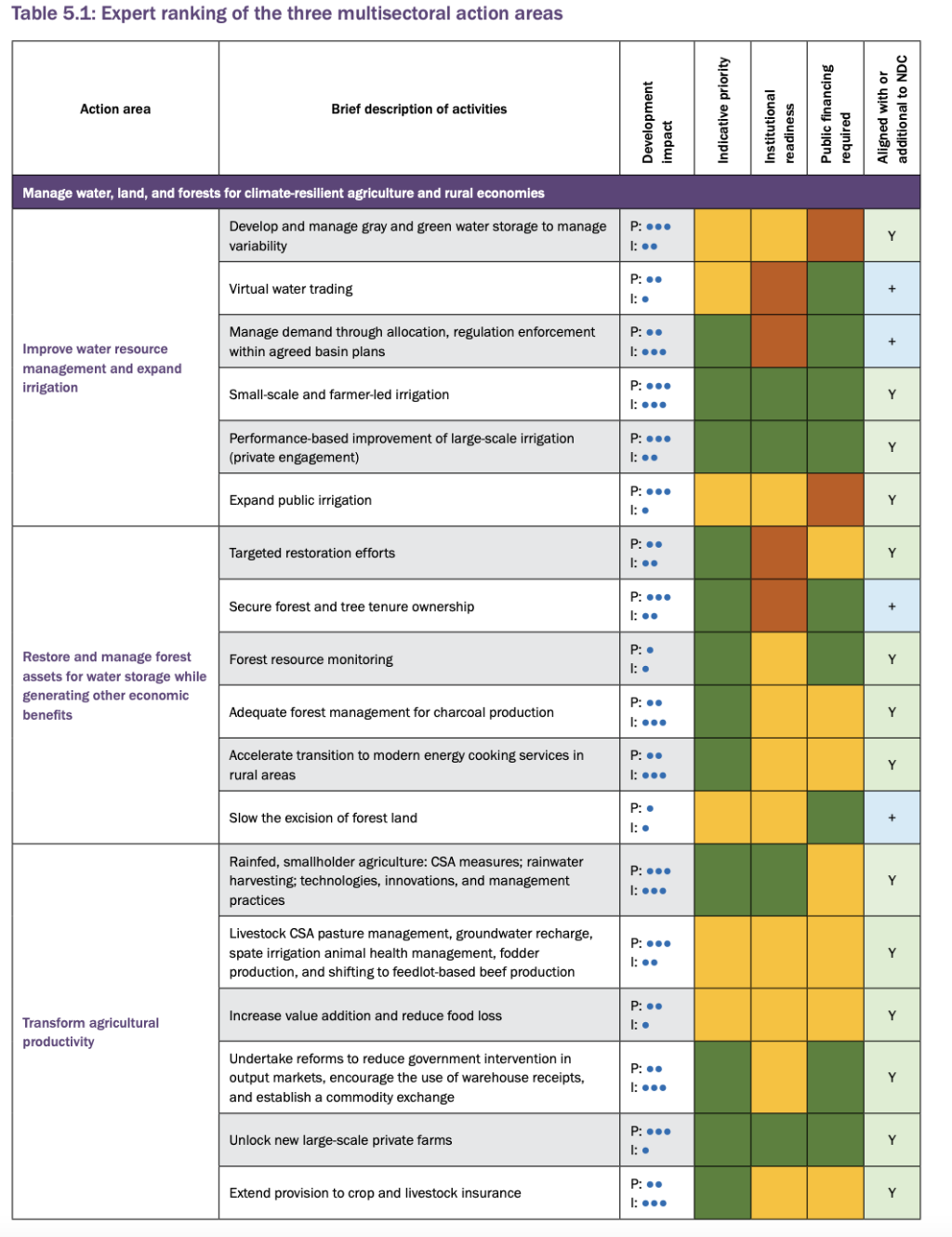

Table 5.1 (extract here on agriculture) provides more information on the expert ranking. The actions that have all green cells are those that could be readily implemented. Actions with a green indicative priority cell require institutional readiness and financing challenges to be address before they can be implemented in the short-term.

| Year of publication | |

| Geographic coverage | Kenya |

| Originally published | 21 Nov 2023 |

| Related organisation(s) | World Bank |

| Knowledge service | Metadata | Global Food and Nutrition Security | Climate extremes and food security | IrrigationClimate-smart agriculture |

| Digital Europa Thesaurus (DET) | climate changepolicymakingclimate change policyadaptation to climate changedisaster risk reductionAgricultureresiliencefood securitysocial protection |