Policymakers are busy bees – an understatement because the work pressure is often high. They work in a highly complex, dynamic, and often conflict-laden environment, where their job is to find effective solutions for the problems arising from today’s ‘VUCA’ world characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. They need good knowledge to address the great challenges of our time as summarised in the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and in the EU to implement the green and digital transition and the post-covid recovery and resilience plans. In short: they need tailor-made knowledge, and they need it ‘now’.

This makes it very difficult, if not impossible, to please them with right and timely knowledge. And it raises the bar for the quality of science-policy mechanisms. For EU policymakers, this is even more difficult as they rely on knowledge providers from 27 countries with their own types of science - policy - society interface, and different traditions on how government organisations like ministries work.

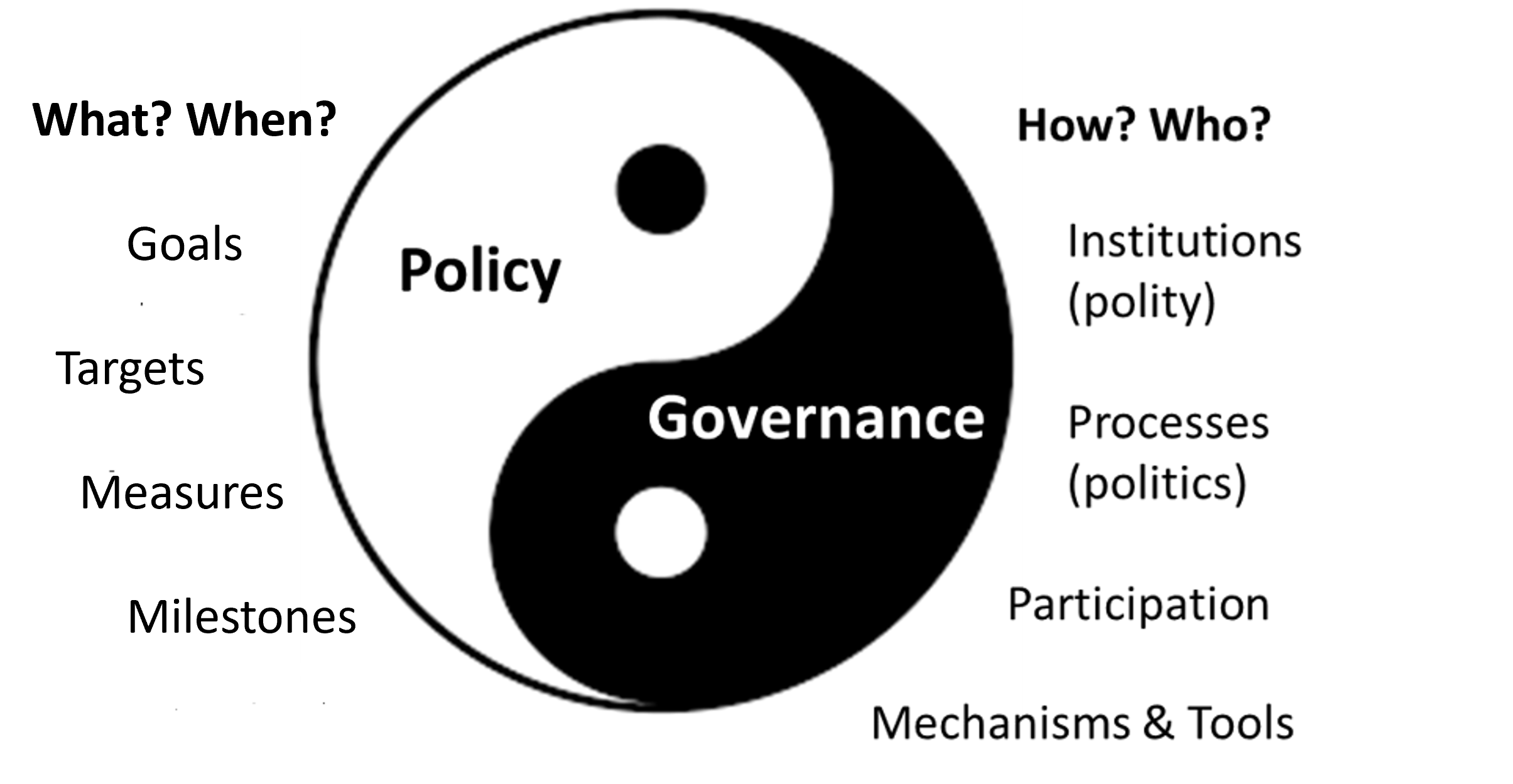

It is therefore important to look at the governance of evidence-informed policymaking. Policy (the ‘what’: goals, targets, measures and milestones) and governance (the ‘how’: who does what, which tools and mechanisms are chosen?) are the ‘yin and yang’ of public administration. They need to be in good balance: without effective governance mechanisms, policies will only be successful by sheer luck.

without effective governance mechanisms, policies will only be successful by sheer luck

Two examples of essential institutional governance arrangements for the science-police-society interface are advisory expert/multi-stakeholder councils, and regulatory impact assessment (RIA).

Advisory councils are intermediaries between science providers and government ‘clients’. Across the EU, their structure and role differ widely, including among others factors their independence. They can only be effective if there is a political will to use scientific evidence, as well as a solution-oriented attitude among science providers. Such intermediary mechanisms must be well-connected with science, policy, and societal actors. Collaborative science for policy systems should have mechanisms to organise joint fact-finding processes about, among others, which knowledge is disputed (and why), and which is commonly agreed. This is essential information for policymakers, if they want to prevent long delays caused by disputes about evidence.

All countries also have some form of RIA procedures, usually in a context of ‘Better Regulation’. Following the good example of the European Commission who decided in April 2021 to mainstream the SDGs in its own impact assessments of major initiatives, RIA procedures are currently being revised in many EU member states. In the first half of 2022, thirteen countries joined a series of peer learning workshops to share and accelerate their attempts to make sustainability knowledge part of the RIA process. This collaboration will continue in an informal peer learning network.

Creating an effective science-to-policy system requires also other governance attributes, such as long-term orientation, participatory mechanisms, multilevel governance, integration of foresight, integrity, transparency, and independent oversight. It requires dynamic, contextualised management and oversight, for which the concept of metagovernance (governance of governance) should be useful.

A science-to-policy system also needs to be monitored, and that is not a small problem. There are no broadly accepted indicators (yet) to measure the quality and performance of science-to-policy systems. Instead, it might be better to focus from the onset on a composite measurement approach, which combines participatory assessment processes and some supporting indicators. Such a ‘joint assessment procedure’ could be adapted to different governance traditions by making it, for example, more expert-based (hierarchical governance culture) or more stakeholder-based (network governance culture). In a market governance context, principles such as competition (ranking, awards) could be used to stimulate self-accountability.

To conclude, in science-policy-society relations, the demand side needs to be taken more into account. A dedicated governance framework would definitely support this.

Louis Meuleman is director at the think tank Public Strategy for Sustainable Development (PS4SD), Brussels. This blog contains contributions from Ingeborg Niestroy – also director at PS4SD – and builds on her report for JRC on Constructing assessment indicator dashboards for evidence-informed policymaking: Insights from the perspective of public administration, institutions, and governance.

Our expert Louis Meuleman is…

Our expert Louis Meuleman is referring to Ingeborg Niestroy's expert report "Constructing assessment indicator dashboards for evidence-informed policymaking: Insights from the perspective of public administration, institutions, and governance" which can be accessed here: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC130062

This is the third and final report from our first stage in the project “Developing an evaluation framework for science for policy ecosystems”. More information about the project can be accessed here: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/projects-activities/developing-ev…

Login (or register) to follow this conversation, and get a Public Profile to add a comment (see Help).

13 Jul 2022 | 01 Aug 2022

Agroecological Territories and Integrated Landscape Approaches to Advancing Food Systems Transitions in Africa

Building resilient food systems

Urban Food Governance at the Subnational Scale

Share this page