French science-for-policy ecosystem updated?

The French science-for-policy ecosystem has recently seen a substantive new initiative. Most notably, in December 2023, President Emmanuel Macron announced the creation of a Presidential Science Council. This Council aims to energize the relationship between researchers and the government and is made of twelve renowned scientists from all disciplines. Inspired by the Scientific Council active during the Covid-19 pandemic, the new structure has the primary goal to establish a central role for science in shaping political decisions.

Ecosystems at the heart of science for policy

The Presidential Science Council, thereby, meets one of the recommendations of the so-called Gillet Report from June 2023, demanded by the Higher Education and Research Minister and published in June 2023: the report calls for ensuring the representation of science at the government level.

Beyond such a highly visible Council, there is more to ensuring an effective use of scientific knowledge in policymaking processes: mobilising science to address complex policy problems requires a systematic reflection on what institutional and professional capacities are needed to connect the world of science and policymaking. In fact, the emerging discourse around science for policy at EU level introduced the term “ecosystems”. This framing widens the science-for-policy discussion from singular mechanisms (e.g. ex-ante impact assessment; opinions of science advisors) or singular organisations (e.g. advisory committees; scientific councils; chief science advisors) to viewing how an entire architecture of science-policy mechanisms and organisations facilitates and shapes the use of scientific knowledge in political decision-making.

The “Gillet” report also casts a wider look at the R&I system and science advice. In fact, it also features the concept of “ecosystem” at its heart. According to the report, addressing research and higher education as an “ecosystem” allows for reassessing and restructuring roles of the different actors in place while also promoting the objective of an evaluation based on impact and efficiency metrics. Yet, the ecosystem framing in the Gillet report focuses mostly on academic knowledge production and innovation (the “supply” side in science-for-policy ecosystems), and remains relatively quiet about the demand side, as well as organisations and mechanisms that aim to connect the two sides.

Mapping the actors in France’s science-for-policy ecosystem

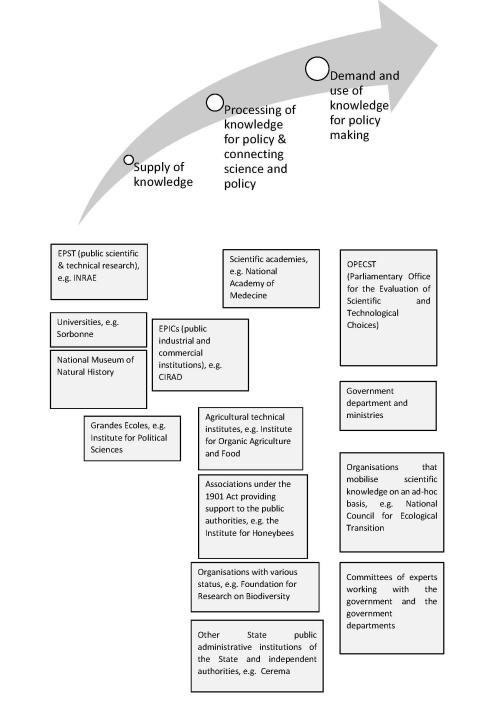

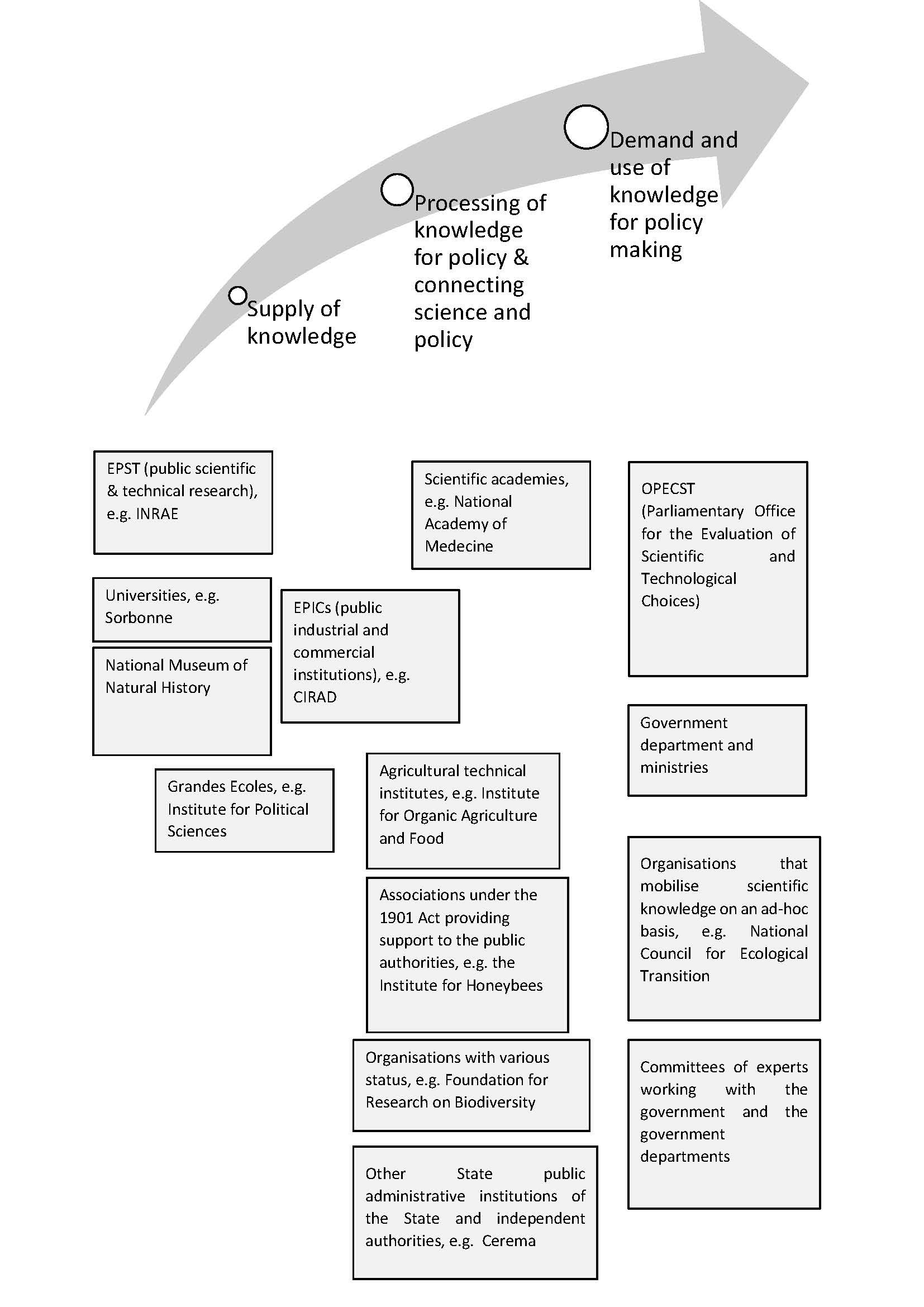

This supply side focus is likely to miss out on some of the key challenges a wider “ecosystem” perspective helps reveal. This wider perspective was applied in another recently published report entitled “Scientific expertise and insights into public policy in France” (FR | EN). This report seeks to capture the complex institutional arrangements underpinning French science-for-policy practices. The report provides an overview of the organizations that operate at the interface between science and policy in France with a special focus on the environment and agriculture-food sectors. It presents a typology of these organizations, as roughly sketched out below (the report provides a more detailed analysis of the different organisations’ role in France’s science-for-policy ecosystem).

In addition to mapping the multiple actors involved at French science for policy, including those providing and producing research, those requesting and using research, and those in-between performing important boundary-spanning work, the report specifically identifies the frictions and challenges emerging in this ecosystem.

Challenges of the French science-for-policy ecosystems

A FIRST important question concerns the relationship between the research organisations and the state authorities, in particular as regards independence, funding and power relations. Are scientists only called upon to provide “instrumental” expert input (oriented towards developing policy options to an already defined policy problem) or can they assume a more “conceptual” role in problem perception/definition and ultimately agenda-setting? Does only “science-on-demand" find their way into policymaking or is other scientific output welcomed and heard by the authorities? How independent, including in their legal status, are research organisations from “their” ministry?

These aspects can become particularly prominent during negotiations between research or boundary organisations (e.g. agencies) and their ministries, either for setting the amount and destination of regular funding, or for setting the formulation of the questions to be dealt with, when specific expertise is demanded.

A SECOND question revolves around what counts as legitimate knowledge and how do different forms of policy-relevant knowledge interact. Different forms of knowledge may come from the academic research community, consulting firms, or when it comes as “regulatory science” even from industry or private laboratories. But what kind of knowledge is seen as most useful and relevant by the evidence users sitting in ministries?

This is a problem that has risen to prominence in the wake of the scandal about the role of private consultancy in orienting public policies. A recent report of a Parliament’s Commission of Inquiry dedicated to the growing influence of private consultancy firms on public policies (2022) has characterized this influence as “sprawling” and has questioned the reasons why decision-makers may prefer these private structures instead skills already available within it, including in research organisms.

A THIRD question concerns the overall architecture of the French science-for-policy ecosystem and how successive crises affect its restructuring. Institutional design is a complex challenge – but getting institutional design under time constraints and public pressure right is extremely difficult. Research and boundary organisms might be demanded to produce evidence-for-policy under the pressure of the last controversy agitating the society to the detriment of wider and prospective reflection on the structure of the ecosystem and its dynamics.

The latest restructuring of the French research ecosystem, which is ongoing, has been partly determined by the failure of the country – as President Macron put it – to produce a successful COVID vaccine. It essentially focuses on contributions of science to industrial innovation, much less to public policies.

Need for systemic thinking about science for policy

At the EU level, a more systematic thinking about science for policy has been initiated, around the concept of science-for-policy ecosystems and building holistically capacities in support of entire ecosystems underpinning evidence-informed policymaking.

The work is inspired by the analyses presented by the Commission in a Staff Working Document (SWD) from 2022 on “Supporting and connecting policymaking in the Member States with scientific research”. In this, the Commission recognizes that the complexity of contemporary policy issues requires a collective, systemic approach to science for policy.

Yet, this is easier said than done: systems require knowledge brokerage and intermediary bodies. Here, the establishment of France’s Presidential Science Council could be seen as one proactive step towards bridging the gap between science and policy.

But this may not be enough, says the SWD: we also need science-for-policy savvy professionals on both government and research side, as well as clear governance principles for evidence use. The latter issue seems relevant in the French context since reflections on independence and power relations at the science-0policy interface should be at the heart of deliberations on how to govern science-for-policy ecosystems. It will be intriguing to see whether the changes introduced by President Macron’s reform will effectively address some of the challenges identified in the analysis of the French science-for-policy ecosystem and more widely at EU level in the Commission’s analysis.

Ideas for turning thinking into actions: Strengthening ecosystems in Member States

Beyond its conceptual relevance, the Staff Working Document furthermore sparked interest in how national science-for-policy ecosystem can be developed and reinforced in practice. To this end, the JRC, together with the OECD, currently implements a multi-country reform project aiming at promoting evidence-informed policymaking within the European Union, which is funded through the European Commission’s Technical Support Instrument managed by DG REFORM.

The project strives to elevate effectiveness of Member States’ public administrations by enhancing their capacity to mobilise and integrate scientific knowledge, evaluation, and evidence in policymaking. Seven Member States take part in the project (CZ, NL, BE, EL, LT, EE, LV), benefitting from in-depth expert analyses of their country’s ecosystem, capacity building workshops to develop skills for scientists for better policy engagement and policymakers to work more effectively with evidence, and mutual learning exercises on foresight, policy evaluation and the use of AI in public administration.

Connecting national debates with European ones

It is important to connect the deliberations and capacity building activities taking place at different levels across Europe. This is because:

- what happens in one country can provide lessons to others – the Commission offers , for instance, opportunities to organize multi-country capacity building projects (e.g. via the aforementioned Technical Support Instrument) or Mutual Learning Exercises (e.g. via the Policy Support Facility);

- insights and instruments developed by the European Commission offer important support – different services offer a wide range of tools, frameworks, materials that can support science-for-policy work in Member States (e.g. the JRC’s work in support of evidence-informed policymaking) and bring together multi-country communities of practitioners around certain governance practices (e.g. foresight);

- wider policy shifts at the EU level in support of evidence-informed policymaking have occurred recently, from the Ghent Declaration of EU-27 ministers responsible for public administration to the Council Conclusions on Science for Policy prepared by the EU-27 research and science ministers, that can further underpin and reinforce national initiatives.

Share this page

Login (or register) to follow this conversation, and get a Public Profile to add a comment (see Help).

19 Mar 2024 | 20 Mar 2024