David Budtz Pedersen from Aalborg University contributes in this blog to the ongoing discussions on how to assess the capacity of science-for-policy ecosystem in a manner that fosters learning and collective deliberation in support of strong and well-connected science-for-policy ecosystems in Europe. In this blog, he introduces the key elements of the guidebook he wrote for evaluators.

Background

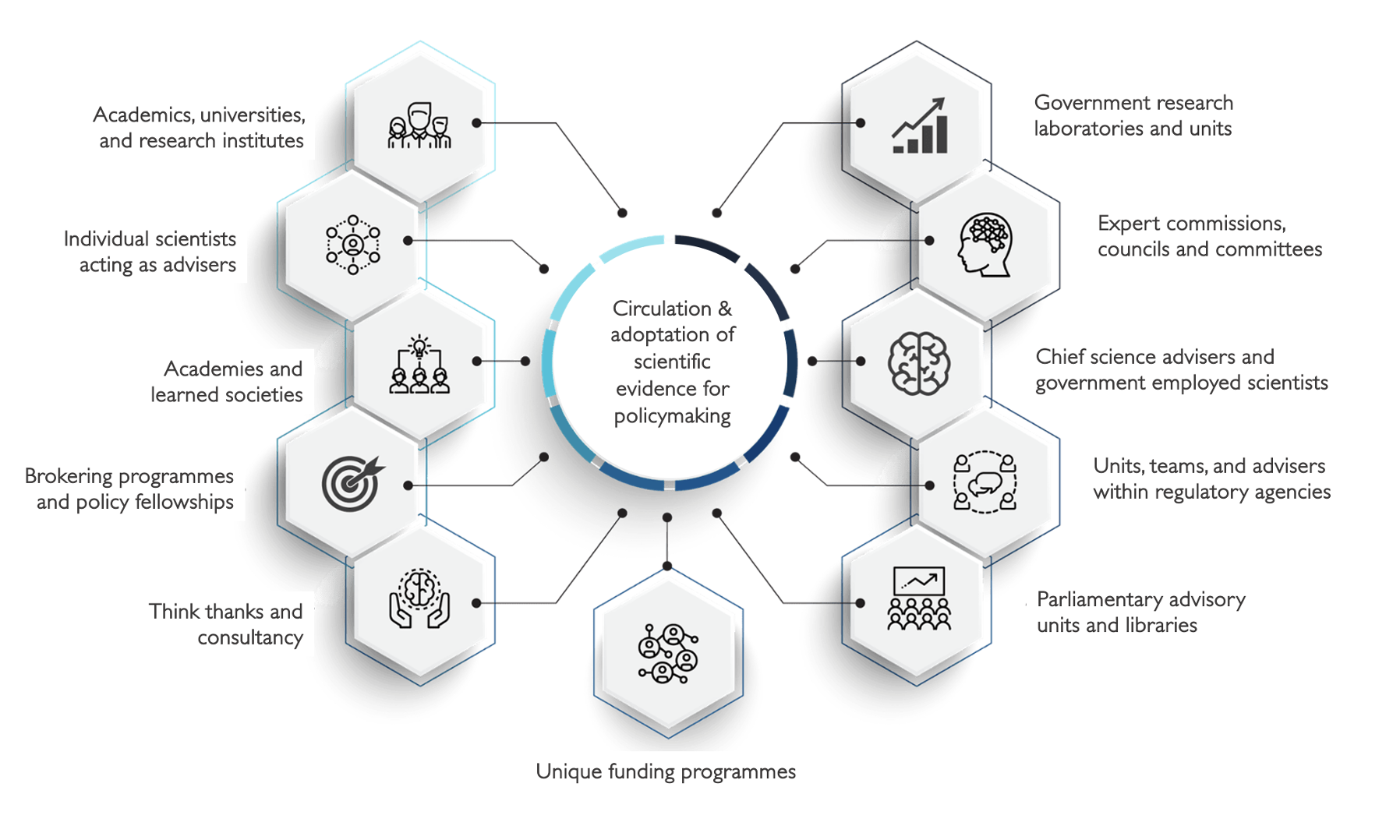

Three years ago, the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) launched a series of thematic workshops focused on mapping and strengthening national ecosystems of science for policy to closely engage with scientists, experts, knowledge brokers and science advisers, policymakers, and other policy practitioners across Europe. A national ecosystem of science for policy consists of an interlinked set of institutions, structures, mechanisms, and functions that interact at different levels to provide scientific evidence for policymaking. These workshops sought to showcase the national composition, covering countries such as France, Portugal, Latvia, Lithuania, Greece, Belgium, Spain, Estonia and Denmark, but also describe cross-national similarities of the advisory ecosystems connecting science with policy. The dialogue demonstrated how European Union (EU) Member States use a wide range of structures and instruments to provide evidence and advice to policymakers, often connected through a complex set of institutions.

To mention a few, the workshops featured examples of the complementary and cross-cutting role of chief scientific advisers, scientific councils for government, science advisers in national ministries, government planning and analysis units, applied research units, parliamentary offices of science and technology, public research institutes, universities, national academies, foresight units, think thanks, regional science-for-policy mechanisms, and other knowledge brokering mechanisms and bodies.

However, the JRC workshop series also demonstrated the risk of fragmentation. In a diverse and uncoordinated ecosystem, weak links can slow down the translation, impact, and quality of evidence in policymaking. This immediately raised the question of evaluation: how can we rethink evaluation and impact assessment to focus on the complex interplay between institutions rather than the performance of individual scientific advisory bodies? To review the institutional capacity of the ecosystem, evaluators need to focus on connectivity, coordination and learning from all actors involved in addition to deliverables provided by individual advisory bodies.

Rethinking evaluation

To better understand the national advisory ecosystems as well as the EU’s support for mobilising knowledge in policymaking, the JRC commissioned a number of reflection papers and pilot studies to provide further inspiration for policymakers and intermediaries at the science-policy interface. Together, workshops and reflection papers have provided input for a newly published guidebook for designing An Evaluation Framework for Institutional Capacity of Science-for-Policy Ecosystems in EU Member States (December 2023).

Access this JRC External Study Report here

This toolkit is designed to support policymakers and evaluators tasked with assessing the capacity of the national science-for-policy ecosystem. For professionals in this role, the guidebook can help shape and inform the assessment of institutions, mechanisms, roles, and structures that public administrations have at their disposal to facilitate the generation of evidence and its circulation and translation in policymaking.

Ideally, a framework for evaluating the institutional capacity of science-for-policy ecosystems should address both the performance of individual institutions as well as their coordination across domains. By adopting the metaphor of an ecosystem, it becomes relevant to design an assessment framework, which identifies individual system components as well as system linkages across the science-policy nexus. This is the starting point for the guidebook.

Science-for-policy ecosystems consist of several dynamic components, which are essential for evaluation. These components are placed along a continuum of different institutions and mechanisms – with some institutions responsible for producing evidence, others for synthesizing and communicating evidence, and again others for adopting evidence in policy. In practice, these institutions are entangled and have overlapping roles and responsibilities. They interact in a fluid and dynamic way with some institutions playing different roles at different times and with different intensities. Opposite to a market metaphor with “supply” and “demand”, an ecosystem consists of closely interlinked, non-linear processes of co-production and co-optation.

Connectivity and knowledge flow

The suggested assessment framework primarily takes the perspective of the Evaluator (governmental staff, consultant, evaluation unit), who is tasked to evaluate a national ecosystem of science for policy, including the formal and informal mechanisms that connect scientific evidence with policy and the processes to make these formal and informal mechanisms effective.

The ecosystem consists of a non-linear space of interactions: the circulation and flow of knowledge across the ecosystem describes the multi-directional links and interactions that enables connectivity between evidence and policy. In this fluid space between internal and external knowledge providers, the crucial metrics of success are coordination and learning. The capacity to connect evidence with policy as well as the capacity to make research and evidence accessible to policymakers are key benchmarks of a well-functioning ecosystem.

Evidence uptake

In a parallel project, an expert group of the European Commission’s Directorate General for Structural Reform Support piloted a set of indicators for measuring the institutional capacity for evidence uptake. This project resulted in two publications: Evidence-informed policymaking – Framing, Assessing and Strengthening EIPM Ecosystems (forthcoming) and Evidence-Informed Policymaking: Building a Conceptual Model and Developing Indicators (2023). These reports show how policymaking is an iterative process across government agencies, ministries, planning units, and other executive and parliamentarian bodies. Adopting evidence in policy is less a question of transferring knowledge from “A” to “B” and more a question of continuously learning and interacting, posing the right questions, identifying uncertainties, and forecasting scenarios and outcomes.

For the purpose of supplementing this work with indicators of knowledge generation, circulation and translation, the new guidebook develops indicators and principles of systemic health, including a checklist of five foundational principles to ensure the legitimacy of the ecosystem, expressed by independence, transparency, responsibility, accountability, and respect for diversity. The evaluation framework includes concrete and actionable guidelines for evaluators to organise a national self-assessment. Central to a well-performing ecosystem is a high frequency of productive interactions between evidence providers and policymakers captured by the following indicators:

- Direct interactions (face-to-face interactions with policymakers, researchers participating in expert advisory panels, experts serving on government commissions, presentations for policy audiences, co-creation events and meetings etc.)

- Indirect interactions (digital and material interactions with policymakers, policy reports, statements, papers, and briefings produced and published, datasets accessed by policymakers, websites, and digital platforms etc.).

- Financial interactions (funding and grants for science-for-policy initiatives, support for policy fellowships, support for joint events and platforms, special calls for projects and programmes to support evidence-informed policy etc.).

- Staff interactions (government appointed scientists, joint appointments of staff, recruitment of policymakers to serve on scientific advisory institutions, staff mobility programmes, exchange programmes etc.)

- Degree of openness, transparency, and collaboration (public availability of evidence reports and advisory statements, declarations of conflict of interests, code of conducts, joint programmes or project with other key evidence providers, citizens, and stakeholders etc.).

The proposed indicators draw on the “productive interactions” framework championed by scholars such as Jack Spaapen, Leonie Van Drooge, Jordi Molas-Gallart, and Paul Benneworth. The indicators are designed to identify opportunities for support, intervention, and more strategic use of resources to improve the circulation of evidence in policy. High-quality evidence is the bedrock of good scientific advice, yet it cannot stand alone. High-quality interactions are equally important to ensure that evidence is used to generate positive societal change. It is our hope that this guidebook can inspire new thinking and experiments within and across the EU national ecosystems.

Building forward better science for policy

Following the publication of the European Commission's Staff Working Document on Supporting and connecting policymaking in the Member States with scientific research in October 2022 and the forthcoming EU Competitiveness Council conclusions on the importance of science in policymaking in December 2023, the EU Science for Policy Conference in October 2023 set a new standard. At the conference, policymakers, science advisors, and researchers agreed that “we need a systematic approach that engage with complex, cross-cutting policy challenges, which means that science advice systems must […] communicate across policy sectors”.

The conference confirmed not only that EU member states must improve the uptake of science in policymaking but that a healthy science-for-policy ecosystem is the basis of European science advice. While Director-General Stephen Quest of the Commission’s Joint Research Centre reminded us of the political importance of science for policy for European democracies (“Trust in democracy and trust in science go hand-in-hand”), Deputy Director-General of DG Research & Innovation Joanna Drake closed the conference by stating that we are witnessing the “beginning of our journey towards a science-for-policy ecosystem in Europe.” Supporting colleagues in Member States to apply ecosystems thinking based on strong foundational principles is one step towards this future. Hopefully, the new evaluation framework will lead to new learning in this space in the years to follow.

David Budtz Pedersen is Professor of Science Communication and Impact Studies, Department of Communication and Psychology at Aalborg University and science policy advisor. The content of the report and this blog posts benefited from the feedback of five critical experts, staff of the European Commission’s JRC and DG REFORM, and Iain Mackie.

Share this page

Login (or register) to follow this conversation, and get a Public Profile to add a comment (see Help).

04 Dec 2023