Today’s information environment could be described as chaotic and overwhelming. The term “drinking from the firehose” captures our everyday experience. Add algorithmic curation for attention maximization, ubiquitous news alerts, a seemingly incessant stream of push messages and a slew of dis- and misinformation casting doubt on everything we think we know and it’s hardly surprising many people to cope or have trouble knowing what truly matters to them.

Enter the public communicator competing for the attention of citizens and wanting to communicate what their institution is doing and why it matters. They are trying to find a way to connect and cut through all the noise to provide often vital information. How can it be done in an effective way? We try to give an answer in our new report on “Trustworthy Public Communication - How communicators can strengthen the future of democracies”.

Public communication (i.e. Communication by public institutions, governments and administrations) is a very broad field and can mean anything from press releases, public speeches, and shiny reports to direct mail exchanges with citizens or journalists, public apps, legal notices, and forms people need to fill out. Each of those interactions with the public is an opportunity for communication. Each of those communications should also follow its own logic, responding to the needs of the audience and the channel employed. However, there are some fundamental principles we can distil from research on what the goals of communication should ideally be.

We have reviewed research from multiple disciplines, including behavioural sciences, public policy, political science, sociology, philosophy, and more, spoken to experts in those fields and public communicators on the front line to find the answers. The work also builds on our previous lessons from our Enlightenment 2.0 research programme where we interrogated our political nature, dived deeper into peoples’ values and identities and the influence of technology on democracy.

There are a number of key messages in our report that are designed to help public communicators to communicate in a more effective and trustworthy way, providing a guiding vision for their work. The key question for public communicators is: what do we communicate for? What is the role of public communication representing public administrations and governments (and we exclude political party communication from this consideration)?

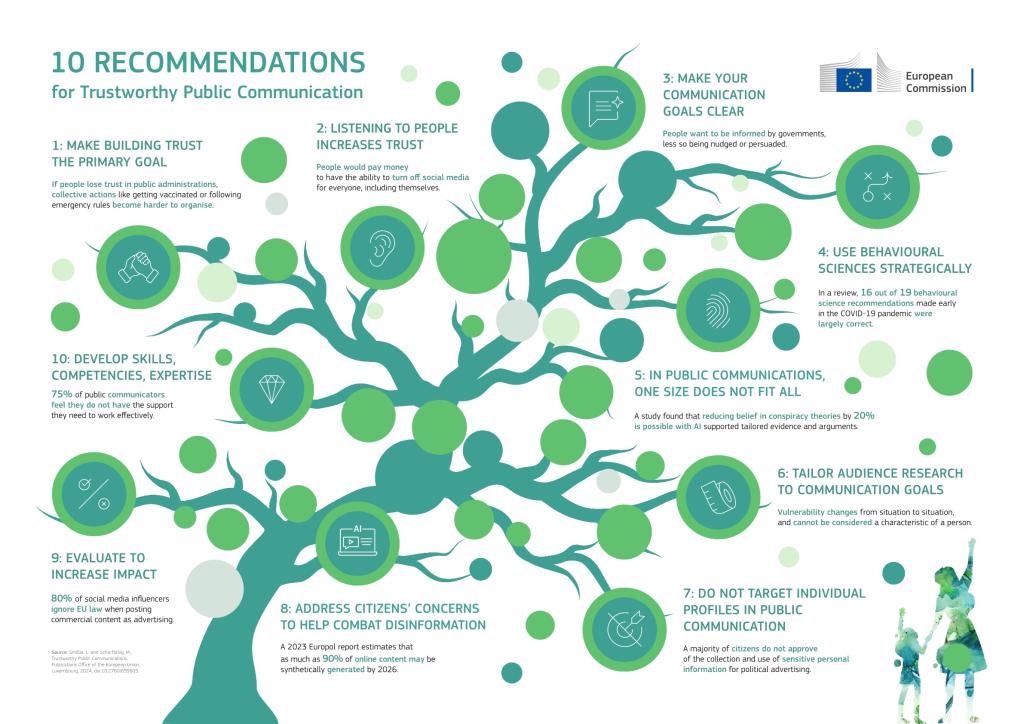

Our answer is that no matter the concrete goal, whether there is a need to inform, persuade, change or listen to the public, communication can only be successful when the communicator is seen as worthy to listen and to talk to. This is reflected in the first key message: “(1) Building and retaining public trust in their public administration, through being trustworthy at all times, should be a public communicator’s primary goal.” People are influenced by those they trust and judge what they read and hear in light of their relationship. Is this information coming from someone they can reasonably trust or is the sender known for shady and unreliable behaviour or outright manipulation? If people distrust the sender, then the information they receive from them will be discounted heavily, no matter how powerful it is. Building and retaining trust as a source of information will therefore help achieve the mission of the public administration.

The best way to increase trust is to act in a trustworthy way at all times, as building trust is much more difficult than losing trust, something that is known as the “asymmetry” principle: A single case of maladministration and bad communication can destroy long built trust relations, as for example people can be relatively insensitive to magnitudes when it comes to moral decision making. Thus “(2) Public communicators should invest more in effective ways of listening to citizens to increase trust in their public administration and democracy.”

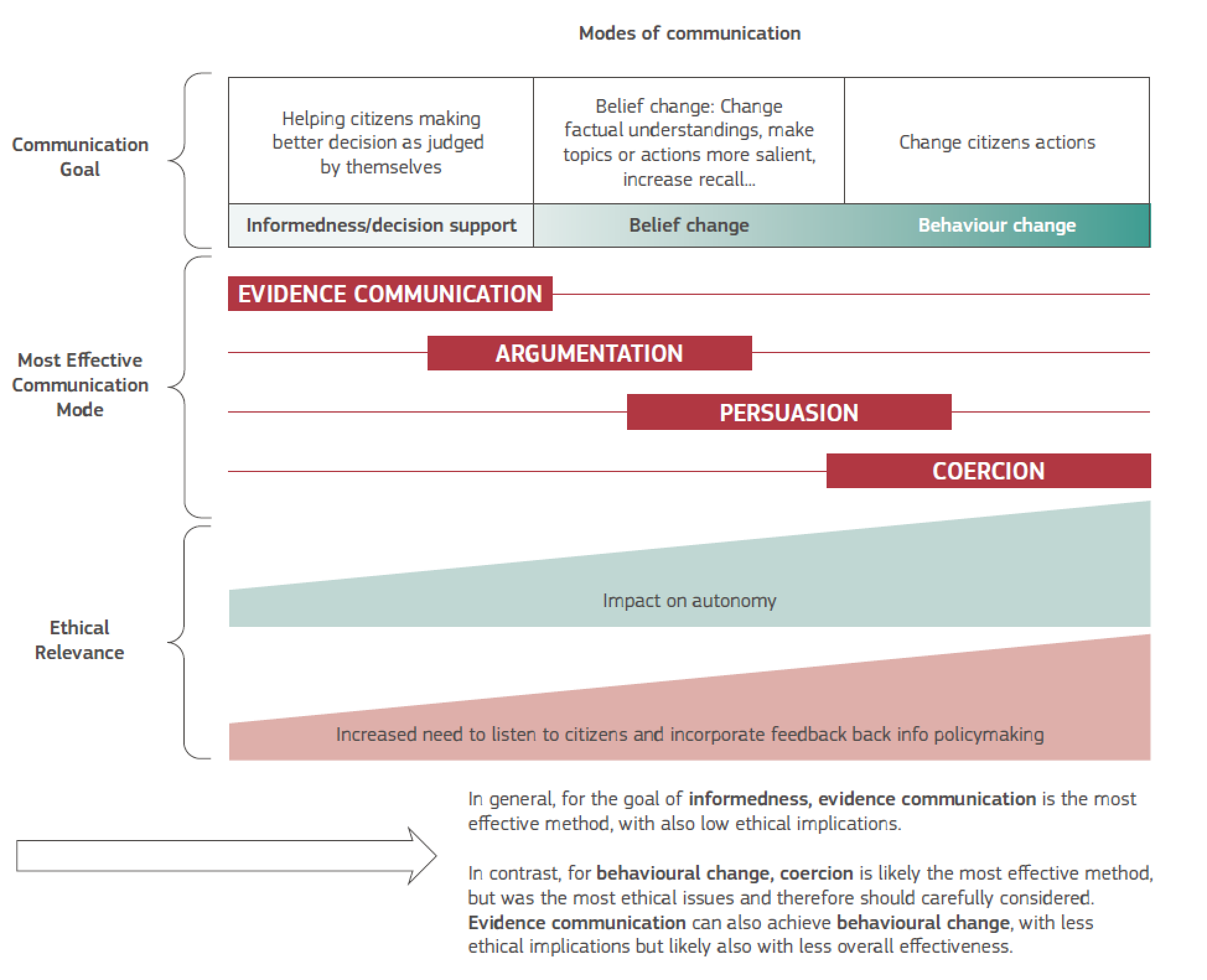

Having established trust by being trustworthy, then we can come to the concrete goal of communication. Answering this question can be broadly divided into two paradigms, the marketer and the enabler. The marketer sees his task as focusing on getting the word out there, persuading and changing behaviour. In contrast, the enabler approaches communication as a facilitator of public dialogue and as providing information and arguments that allows citizens to make up their own mind.

There are merits and drawbacks to both paradigms, and usually public communication is neither purely one nor the other. We reflect this in our report, proposing a spectrum of communication goals and accompanying modes. The primary reflection that is needed by the public administration, which means policymakers together with communicators, is to decide when addressing a policy problem what the goal of the communication is. Is it to enable citizens to make their own decisions, is to persuade or change behaviour or is it to gather more information from the audience because not enough is known about local or other specificities?

In line with this spectrum of goals, we also offer explanations for which modes of communication are most effective in reaching this goal, for example, evidence communication may serve “informedness” as a goal best. Importantly, we also highlight that the ethical implications and therefore the needs for justification of the communication (and related policies) increase along the spectrum. Governments and public administrations can be argued to have an obligation to change peoples’ behaviour in some areas, be it through persuasion, nudging or even coercion. For example, it is reasonable to expect persuasive action on reducing criminal behaviour, encouraging safe driving, improving vaccination rates against communicable diseases or simply to get citizens to pay their taxes. We offer a full chapter on behavioural insights, many of which can directly be applied to communication, referring to our key messages “(4) If behaviour change is the communication goal, behavioural sciences should guide the selection of the most appropriate tools”.

Behavioural sciences can play a dual role on the spectrum between marketeer and enabler. On the one hand, the dominant voices from behavioural sciences are usually found on the marketeer side, partially because behavioural sciences are focusing by definition on explaining and changing behaviour. Nudges are firmly following in this tradition, where established goals of the administration are sought to be better implemented by recognizing the true nature of human decision making, rather than following some “rational” model of choice. These nudges are usually broadly supported in Europe, including nudges like decreasing obesity through food labelling, increasing organ donations through prompting active choice, reducing smoking through graphical images or increasing retirement savings using default saving plans. But as the popularity of these tools increases, so does the range of application, not all of which may benefit from such large public support. It is essential therefore to also use the important insights from behavioural sciences to better understand citizens, be it in abstract through better understanding their values, or concrete by engaging with them to define the goals of nudges. Alternatively, use behavioural sciences to develop boosts – promoting capabilities that citizens can use in multiple contexts.

Unfortunately, in reality a lot of public communication still appears to be following a different mode of “silence, silence, silence, press release: We achieved it all, ribbon cutting, silence.” Whether driven by fear of public repercussions to non-agreed and non-perfect policy solutions, a wish to not be seen as vulnerable or directionless or simply by the lack of resources, this is a potentially dangerous mode of communication. Dis- and misinformation thrives in information vacuums, filling vital gaps of legitimate public interest with wrong, harmful and hateful information that will harm the public administration more than demonstrating a more open, transparent and engaging mode of communication that is however less assertive. Our key message on this is “(8) Public communicators should acknowledge public concerns pre-emptively, before policy solutions have been developed; this includes strategies to combat mis- and disinformation.”

The most successful public communicators will be the ones successfully navigating the different goals and modes of communication, keeping in mind that they all have their different merits and pitfalls. For example, the marketer's methods can be highly effective in cutting through the noise and capturing attention in our oversaturated media landscape, but, it can sometimes come across as insincere or manipulative if not executed with care and ethical consideration. On the other hand, it is clear that the enabler, while fostering deeper engagement and understanding, faces challenges in scaling their impact or in engaging audiences who are used to more direct and assertive forms of communication, or not interested in engaging at all. The new digital formats of online simultaneous and multilingual discussions seem a particularly promising way to overcome this latter challenge though.

What now? If you are a public communicator and you are currently working on a piece, we have a practical test in the report, the TARES test (p. 21), that could be used by institutions to have a general ethical framework. But for now, just ask yourself: How democratic is your article? Does it enable public debate by informing, or is it designed to make you and your organisation look good? What would you want from the communication if you were “just” a citizen? Perhaps, we can build a reputation for being trustworthy organisations by demonstrating meaningful listening to citizens and stakeholders, respecting their input together with input from scientists and experts to achieve sustainable positive impact? After all, the belief that public administrations care about citizens input is one of the most powerful predictors of trust in the administration as shown in a large-scale survey by the OECD.

One thing is clear though, considering the fast-paced change in the global information ecosystem. Most public administrators we talked to said that public communication today is not like anything they learned when they started their jobs, even for those who are not yet working for very long in their profession. There are only a few jobs that have undergone a more thorough transformation. Therefore, we recommend “(10) New challenges require new skills, competences and centres of expertise to support the public communication profession”.

Share this page

Login (or register) to follow this conversation, and get a Public Profile to add a comment (see Help).

09 Oct 2024 | 14 Oct 2024