Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in the blog articles belong solely to the author of the content, and do not necessarily reflect the European Commission's perspectives on the issue.

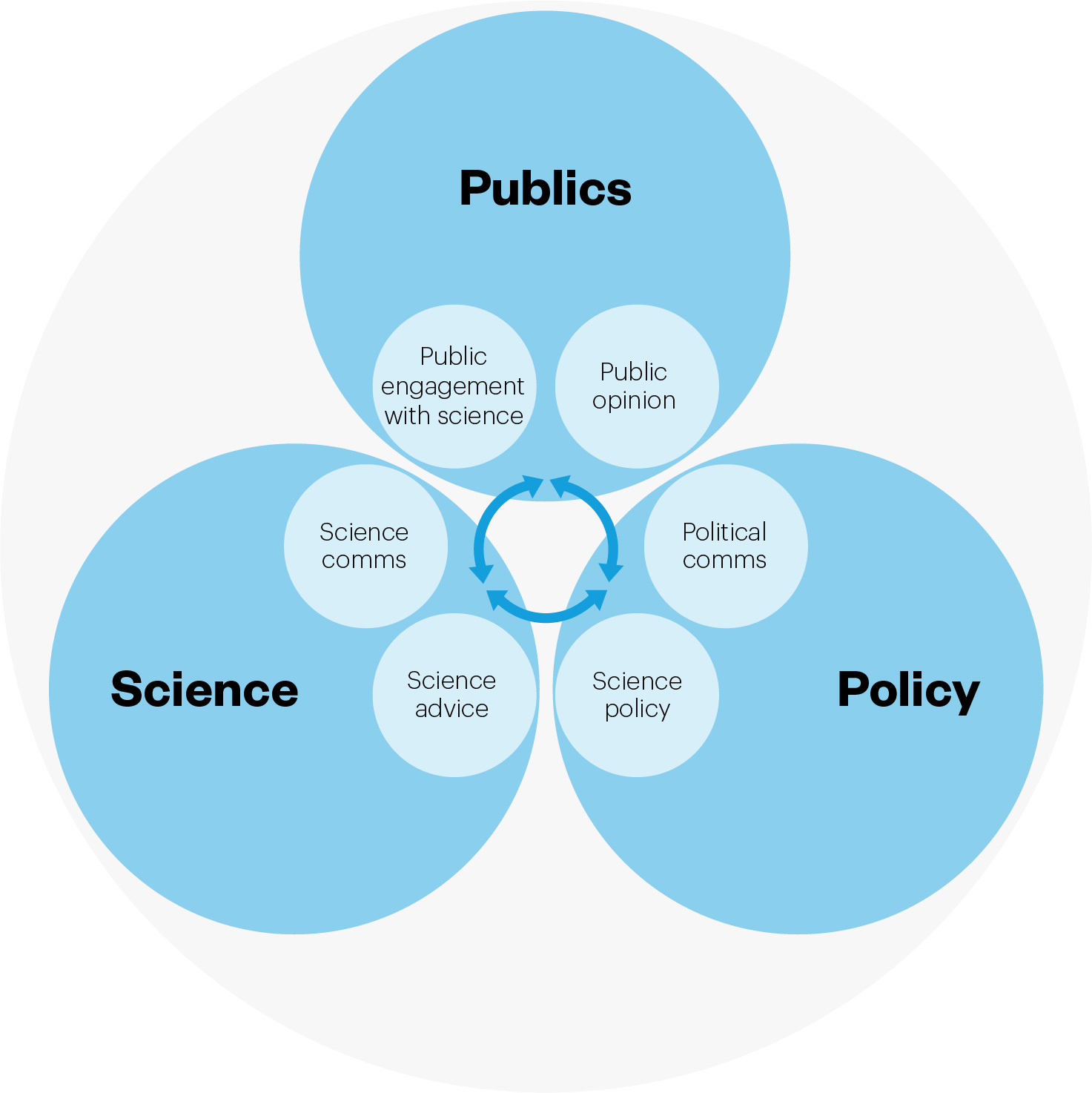

Science increasingly plays a central role in public debates on policy, as starkly exposed during the Covid-19 pandemic. The recent British Academy report, Public trust in science-for-policymaking: Understanding and enhancing the role of science in public policy debate in the UK, explored the conditions under which the public view science as relevant and trustworthy in policymaking and what can be done to enhance the role of science in public policy debate. Not all policy issues feature significant contestation in public debate and have a relevant body of science informing it. But those that do stand out – Covid-19, genetic modification (GM), climate change, AI regulation and precision breeding are just a few recent examples.

The British Academy’s report set out findings based on insights from two research projects, stakeholder engagement and expert deliberation running over the course of 18 months. Three headlines stand out.

First, policymakers play a central role in framing policy discussions, especially at the early stages as new policy issues emerge. They should clearly articulate the role of science in informing policy responses. Second, in explaining the role of science in policy, policymakers should not underestimate the public’s desire for nuance and transparency in the role of science-for-policymaking. This can involve being open to communicating uncertainties and acknowledging knowledge gaps. Third, policymakers should recognise that more information will not in itself increase trust, and avoid a simplified ‘follow-the-science’ approach. Indeed, there is a diversity of considerations and evidence shaping policy development, and building trust in science also requires policymakers, researchers and knowledge brokers to be clear that expert knowledge is not the only or necessarily main consideration in determining policy.

Despite consistent research findings (e.g. PERITIA, SAPEA (2019), Owens (2015)) that reflect these headlines over recent decades, increasing understanding of these issues is still part of the challenge. The role of framing is a good starting point: framing will influence how far scientific evidence is seen as relevant to policy deliberation, and there are key windows of opportunity to shape these frames. Values and interests also play a role in framing and policymakers need to communicate how they have factored in scientific evidence alongside these wider values and interests to avoid publics simply discounting that evidence. Meanwhile, policymakers should also be aware of different levels of trust in scientific sources, which may vary across different policy areas. Citizen engagement has the potential to generate greater levels of trust here.

Some of the issues can boil down to a failure to find effective ways to disagree in public – for example, in debates on GM food, scientific findings from distinct fields have been marshalled by different protagonists in highly selective and sometimes distorting ways. Engagement across disciplines is crucial; and there are gaps in understanding underlying attitudes among different publics. The ‘information deficit model’ that suggests more information will shift attitudes is largely discounted amongst the research community, yet it prevails in some policy settings. The project’s public attitudes research suggests that there is a public willingness to engage with scientific content, but this must be done with attention to the issues above.

Beyond building understanding, how science is communicated and brokered are essential factors in acting on these findings. In particular, there are complex issues to navigate around acknowledging uncertainty. Policymakers should invoke scientific findings with authority, setting out transparently how a body of evidence has been marshalled and used; but not in an ‘authoritarian’ way that invokes science in a simplistic or selective manner. Meanwhile, in a rapidly developing science communication environment and the rise of social media, relatability is a new currency that can have a big influence on trustworthiness (see Boswell & Morgan Jones (2024)). Here though, there are risks in grounding trust in a set of characteristics not related to the quality of the science, highlighting the need for those with scientific qualifications to learn, adapt and improve appropriately the accessibility of their engagement and communication.

Bringing these findings together, the report puts forward ten considerations for policymakers, researchers and science brokers to consider for how to strengthen public interest and trust in science-for-policymaking. Policymakers and researchers need to consider carefully how these relate to the specific context, issues and institutional arrangements in a given policy area, but they provide a useful starting point and the report elaborates on each one in its conclusions.

Trust is at the heart of the report. It closes with reflections and implications for grounding trust in science-for-policy. First and foremost, the report highlights the risks of a mistrust in politics spilling over into science. If this occurs, science could lose its authority and traction as a resource for informing policymaking, so science must be invoked in ways which augment trust. Without this, we may be inhibited in our collective ability to solve the very substantial problems facing our societies, economies and environments.

Whether they are policymakers, researchers or knowledge brokers, all those involved in science-for-policymaking share a responsibility for stewardship of public trust that relies on increasing their understanding of these issues and acting on that knowledge. The British Academy’s report, we hope, provides useful insights and starting points to support this crucial endeavour.

Login (or register) to follow this conversation, and get a Public Profile to add a comment (see Help).

08 Nov 2024

Climate Change, Green Economy, and Agriculture - A Development Pathway towards Food Security and Climate Resilient Sub-Saharan African Countries

Impact of technology transfer on food security in developing territories: a bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review

Infrastructure, knowledge and climate resilience technologies enhancing food security: Evidence from Northern Pakistan

Share this page