By Joe Jones, Alexandra Trofimov, Michael Wilde & Jon Williamson. We are a research team based at the University of Kent and King’s College London, with an interest in evidence synthesis in social policy, medicine and law. In this blog post, we introduce Evidence-Based Policy + (EBP+), a methodology for exploiting scientific evidence alongside the experimental and observational studies that are the focus of orthodox evidence-based policy evaluations. We look briefly at Covid-19 face-mask mandates to illustrate how this methodology works.

The need to integrate different kinds of scientific evidence in policy

The need to integrate scientific evidence into policymaking has become increasingly clear since the first EU Commission Communication promoting ‘better regulation’ in 2002, and more recently via an update of ‘better regulation’ that identifies scientific evidence as a cornerstone of Better Regulation. Since then, the problems policymakers need to address have become increasingly complex, requiring robust scientific data, at a time when public trust in government and science is precarious. The global Covid-19 pandemic, and the varied responses to it by EU member states, provides perhaps the clearest recent example of the urgent need for policymakers to have access to high quality, robust, and consistent scientific evidence, to ensure consistent and effective policy design across the EU as a whole. This recognition is widely shared at EU level, as expressed in the 2022 Commission Staff Working Paper on Science for Policy and recent endorsement of the need to build capacity for evidence-informed policymaking by EU-27 governments.

How to address the challenge of integrating science into policy: EBP+

While the need to integrate scientific evidence in policymaking is clear, there isn’t a universally accepted framework for doing so in practice. Orthodox evidence-based approaches take Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) as the gold standard of evidence. Others argue that social policy issues require theory-based methods to understand the complexities of policy interventions. These divisions may only further decrease trust in science at this critical time.

EBP+ offers a broader framework within which both orthodox and theory-based methods can sit. EBP+ also provides a systematic account of how to integrate and evaluate these different types of evidence. EBP+ can offer consistency and objectivity in policy evaluation, and could yield a unified approach that increases public trust in scientifically-informed policy.

Evidential Pluralism as a methodology for integrating different kinds of scientific evidence in policy

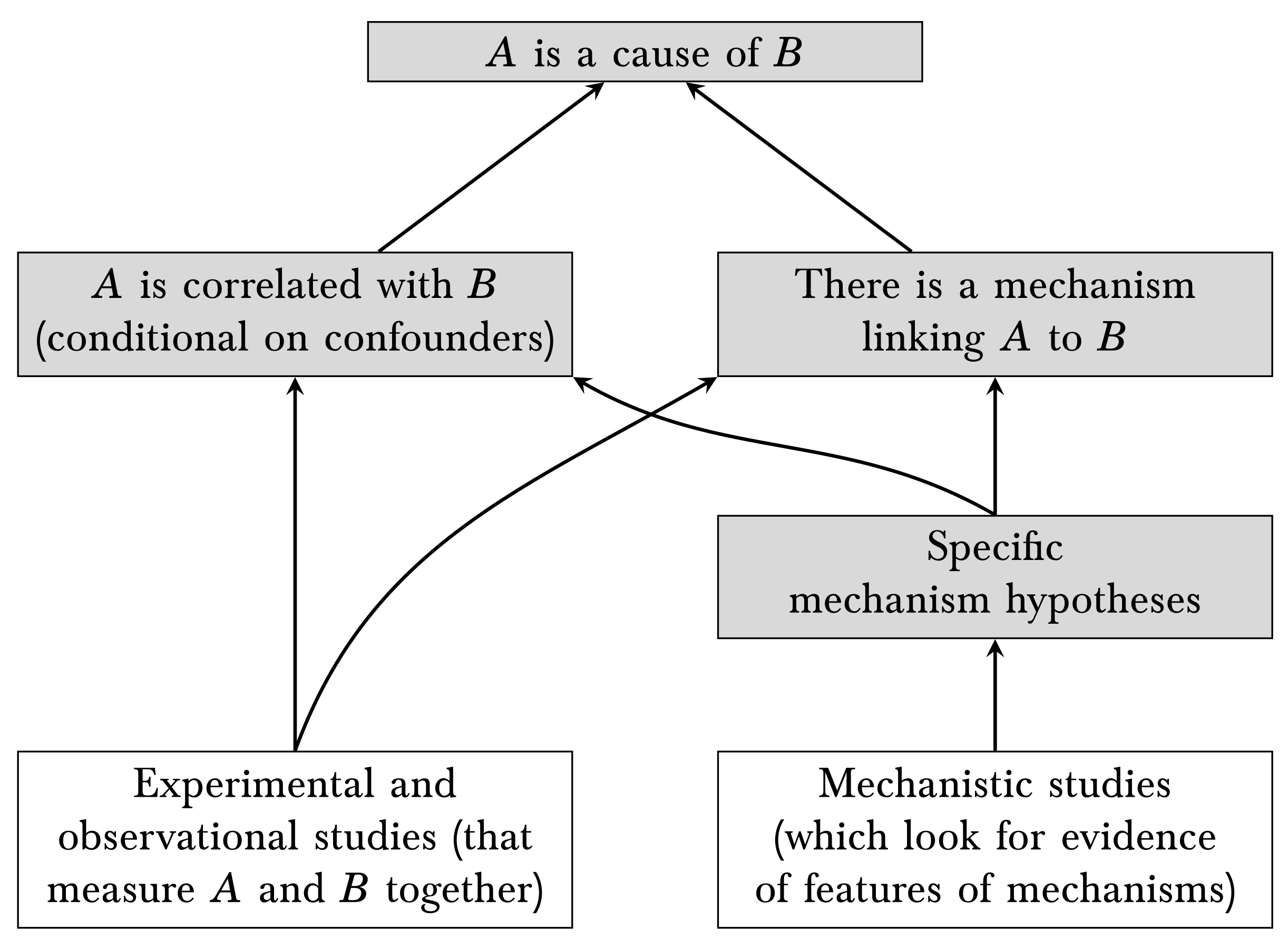

EBP+ is motivated by Evidential Pluralism, a philosophical theory of causal enquiry that has been developed over the last 15 years. Evidential Pluralism encompasses two key claims. The first, object pluralism, says that establishing that A is a cause of B (e.g., that a policy intervention causes a specific outcome) requires establishing both that A and B are appropriately correlated and that there is some mechanism which links the two and which can account for the extent of the correlation. The second claim, study pluralism, maintains that assessing whether A is a cause of B requires assessing both association studies (studies that repeatedly measure A and B, together with potential confounders, to measure their association) and mechanistic studies (studies of features of the mechanisms linking A to B), where available.

Previously, Evidential Pluralism has been applied to medicine, where it leads to a development of evidence-based medicine called EBM+. An example of an organisation whose evaluation procedures conform closely to EBM+ is the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Evidential Pluralism has now begun to be applied to evidence-based policy evaluation, leading to the EBP+ approach to evaluation. EBP+ provides a systematic framework for integrating scientific evidence in policy evaluation: the sciences generate mechanistic evidence, and this evidence plays a central role in an EBP+ evaluation.

How to apply EBP+ in practice: The case of face masks

A narrow focus on experimental studies, especially RCTs, resulted in controversy and uncertainty concerning the effectiveness of public health interventions to reduce the spread of Covid-19, including public face-mask mandates. This prompted calls for a more inclusive approach to evidence in responding to the novel, complex and rapidly changing problem of Covid-19 (Aronson et al., 2020; Greenhalgh et al., 2022; Mormina, 2022). This case study therefore provides a good example of the need for and benefits of EBP+.

The causal claim of interest is that a legal requirement to wear a face mask in public reduces the prevalence of symptomatic Covid-19 infections and thereby reduces the number of hospitalizations and deaths. According to EBP+, assessing this causal claim requires evidence of correlation and evidence of mechanisms.

The correlation claim is that a legal requirement to wear a face mask in public is negatively correlated with symptomatic infections, conditional on potential confounders.

A plausible mechanism hypothesis is that a legal requirement to wear a face mask in public increases the use of face masks which in turn reduces the prevalence of Covid-19 which reduces the prevalence of symptomatic covid infections and thereby the number of hospitalizations and deaths.

A plausible hypothesised counteracting mechanism is that a legal requirement to wear a face mask in public will decrease compliance with other public health interventions, such as social distancing. This in turn would result in an increase in the number of symptomatic infections compared to the number that would have occurred if the legal requirement to wear a face mask had not been introduced.

On the basis of available evidence, we found that quantitative studies detect a robust correlation across contexts. We also found that a combination of quantitative and qualitative studies provisionally establish the hypothesised mechanism of action, and they undermine t the hypothesised counteracting mechanism. The strength of evidence of correlation further increases confidence in the mechanism of action. Overall, the combination of evidence of correlation and evidence of mechanisms establishes the effectiveness of face mask mandates (Trofimov and Williamson, forthcoming, summarised here).

This evaluation of the effectiveness of face mask mandates considered a wide range of evidence, including from physics, biology, medicine, epidemiology, psychology, and social and behavioural sciences.

Note that EBP+ can also be used to point to gaps in the evidence base for a policy. Examples that we have looked at include: (i) establishing whether online fake news has a detrimental effect on behaviour, in particular, vaccination behaviour; (ii) establishing the effectiveness of minimum unit pricing for alcohol for reducing deaths; (iii) establishing the effectiveness of a universal basic income; (iv) analysing awarding gaps in higher education. More details of these examples can be found in our guide to EBP+: Integrating Heterogeneous Evidence Using Evidential Pluralism. Crucially, the examples involve integrating evidence from diverse sciences.

Mainstreaming EBP+

EBP+ applies the philosophy of Evidential Pluralism to evidence-based policy evaluation and it provides a vision for basing policies on high quality science. But how can EBP+ become more widely implemented?

Firstly, we need to revisit our processes and procedures. We need policy evaluation procedures that routinely scrutinise scientific mechanistic evidence alongside experimental and observational studies when evaluating what works. EBP+ provides a step-by-step procedure for doing this, and this procedure needs to embedded into our systems.

Second, we need to better exploit scientific skills and competences when designing and evaluating policies. Policy-relevant mechanistic evidence is produced by a wide range of scientific disciplines, as we saw above when considering face-mask mandates. We may need to consult scientists from across these disciplines to get a thorough understanding of the quality of the available mechanistic studies and to help evaluate mechanistic hypotheses. It needs to be more widely recognised that proper policy evaluation requires a broad range of scientific expertise.

Share this page

Login (or register) to follow this conversation, and get a Public Profile to add a comment (see Help).

15 Mar 2024